Poverty has been overlooked as an issue in the General Election campaign. Let's change that and Stand Against Poverty

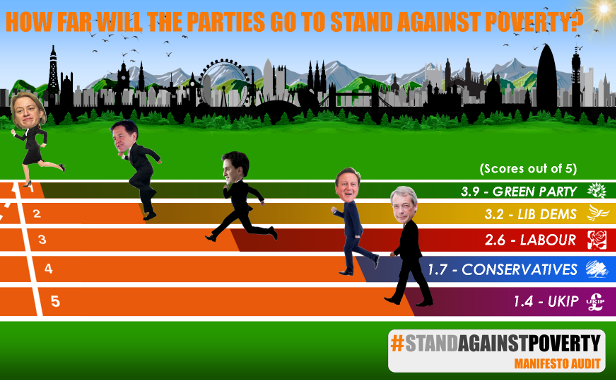

Ahead of the General Election, a group of leading academics has completed an audit of the political parties’ manifestos to assess the impact of their policies on UK and global poverty. The audit has been conducted by Academics Stand Against Poverty (ASAP) UK, a group of scholars, teachers and students united in a common resolve to end poverty everywhere.

With approximately 13 million people currently living in poverty in the UK, we believe it is time to shift the debate about poverty, which should not be seen as inevitable. Our aim is to transform the nature of information about poverty and support interested citizens make informed decisions when they vote on 7th May.

We define poverty as the absence of a flourishing life. ASAP UK has reviewed the key policy areas and cross-cutting themes of this year’s main party manifestos - including housing, education, health, immigration and international aid. We assess the extent to which these policies will enable British society to flourish within environmental limits, both now and in future, through a simple scoring system and qualitative analysis.

The volunteer authors, peer reviewers and contributors come from over twenty different universities. Each party and policy area has been scored, allowing voters to see clearly which parties are taking the strongest stand against poverty on the issues they are interested in.

We are urging interested voters to consider the impact of parties’ policies on poverty when they vote on 7th May. Help spread the word and discuss our findings by following us on Twitter at @AcademicsStand and tweet using the hashtag #StandAgainstPoverty. Share it with friends, family and colleagues and make a stand today.

This is a project convened by the UK chapter of Academics Stand Against Poverty (ASAP), an international association focused on helping researchers and teachers enhance their impact on poverty.

Thank you for reading this poverty audit. Academics Stand Against Poverty UK have prepared it aiming to transform the nature of information about poverty in time to be available to citizens ahead of the 7th May UK General Election. We do not claim this document is a definitive guide to or even the expert view on the poverty impact of the different UK political parties’ policies. But we hope this innovative multidisciplinary poverty audit puts a stake in the ground. With approximately 13 million people currently living in poverty in the UK, it’s time to ensure poverty is not seen as inevitable.1 Poverty must be a core criterion against which we evaluate political parties’ commitments.

We believe that there is both an unmet need and a demand for quality independent assessment of the pledges coming from political parties. We hope that you – as an individual concerned by poverty – will find our results help you think through your choices. We also intend to track the next government’s commitments during its new term.

Who is “we”? Over fifty volunteers – academics from 21 UK universities, peer reviewers, students, communications experts, policy people – have come together on an Academics Stand Against Poverty UK platform over the past three months. Our common objective has been to pull together impartial, rigorous and evidence-based analysis of the political parties’ promises on domestic and international poverty, and share it in an understandable way. We believe that the impact of the financial crisis and subsequent austerity policies means that understanding policy implications for poverty is even more important than ever. We are concerned by anecdotal evidence that the UK’s Lobbying Act is silencing the voices that would normally advocate policies that address the needs of the poor. We are not convinced that the UK political parties’ practice of publishing over 500 pages of manifesto commitments three weeks before the election is a helpful way of supporting citizens in their decision on how to vote.

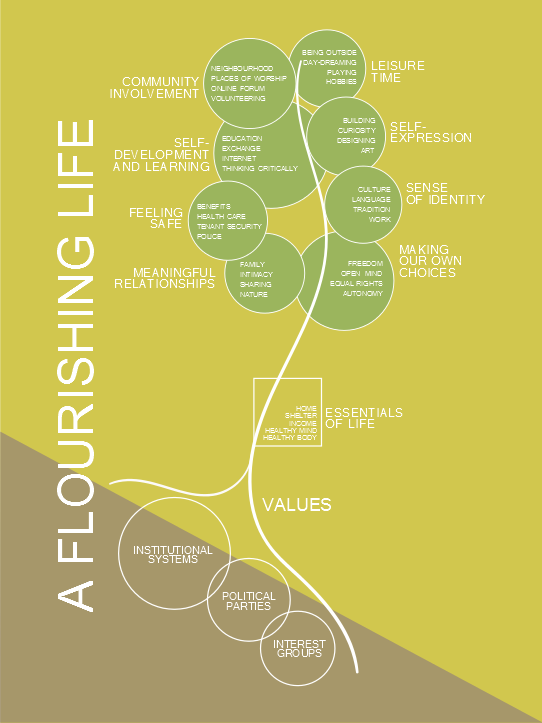

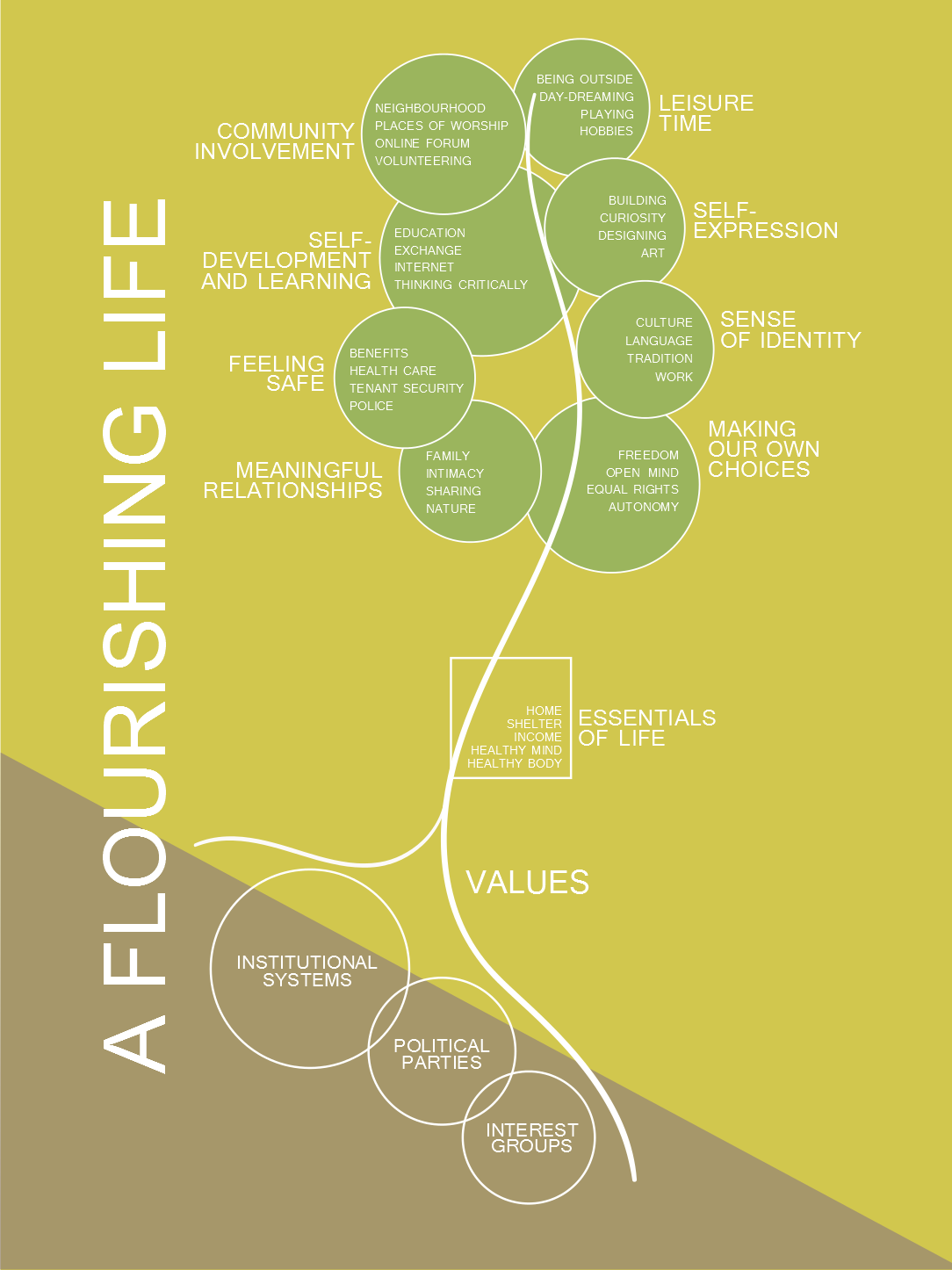

The global and multidisciplinary nature of our network has inspired us: when pulling together, we have drawn upon international understandings of poverty. We believe that it is best understood not only as the absence or lack of access to resources, but also as a wider set of constraints on the ability of individuals to lead flourishing lives (as per Sen and Boltvinik’s approaches). We used this thinking in our framework to assess the extent to which party manifestos provide the confidence that policies will enable British society to flourish in the world, within environmental limits, both now and in future. In the year where the universally-applicable Sustainable Development Goals are replacing the developing country-focused Millennium Development Goals, we felt it was right to acknowledge the global contributions to understanding the nature of poverty.

In the following chapters, you will read about 14 different policy areas, assessing the policies of five of the main parties. You can read what we think are some of the most interesting findings and our scores. We have published separately a discussion of our narrative and definitions of poverty and flourishing on our website at wwwUKPovertyAudit.org. There you can also find another report on the methodology, including how the audit was conducted, how these themes were chosen and their relation to poverty. The process the authors and peer-reviewers followed is described in detail, including reviewing the costs implications of the policies. We covered Conservative, Green, Labour, Lib Dem, and UKIP since they were the parties who were either likely to form majority governments, or who as a minority partner, would make significantly different policy demands in key areas as part of a coalition agreement. SNP’s manifesto, out a week after the others, was too late to be included but was part of the original lineup. Next General Election, we hope to provide an even more complete picture.

Finally, we would like to take the opportunity to say thank you to all our volunteers: our authors, the advisory board, our peer reviewers, everyone who has helped the endeavour. But in particular, we would like to thank the core team who put heroic amounts of time and energy since we met to plan this last year. To Anna Carey, Jon Finka, Iason Gabriel, Debjani Ghosh, Michelle Gillan, Maia Kan Laura Kyrke-Smith, Sara Mahmoud, Francesca Roettger Moreda, Julia Oertli, Sandy Schuman, Tuukka Toivonen, Mann Virdee, Sophie Walsh, and other key individuals – thank you for your commitment. And thanks to Keith Horton for his mentoring role and the wider ASAP Global team.

Please read this audit. Please dispute our scores. Please tell us if you agree with our assessments. But above all, please contribute to a public debate on the impact of parties’ policies on poverty.

Cat Tully and Meera Tiwari Academics Stand Against Poverty UK Co-Chairs

The delay in publication of the manifestos means there has been little time for serious analysis and debate. Voters will have three weeks to evaluate 500 pages of proposals. We believe that citizens would engage more with the substance of parties’ policies if their proposals were published earlier. Our aim has therefore been to get helpful information comparing the parties out to citizens two weeks before the election.

We will not resolve the debate about poverty – it’s a widely used but contested word – but using a broad definition, we hope to assess the impact of policies in the real world across a variety of public policy areas and services that citizens value. Our approach is therefore multidisciplinary and systematic. The final report is intended to help citizens arrive at their own conclusions about what is on offer.

We define poverty as the inability to flourish. Poverty occurs when needs cannot be fulfilled. These include feeling safe, having opportunities for self-development and learning, and having the freedom to make your own choices. In short, poverty cannot be understood simply as the failure to attain a minimum level of income. We therefore have used a broad and relative definition of poverty that looks at it as a social and dynamic phenomenon. More information and a report on the definition and approach can be found at www.UKPovertyAudit.org.

Contributors were selected based on their areas of expertise and interest. We developed guidelines for these contributors, which were reviewed. All the contributions were peer reviewed by a separate group of academics, who assessed them for theoretical soundness, analytical rigour, political neutrality and writing style. We commissioned two migration chapters to explore fully the individual and security aspects of a policy area of high focus in this election. And the authors examined the cost implications of all policies as part of the assessment process. More information and a report on the methodology can be found at www.UKPovertyAudit.org.

The people that came together under the ASAP UK Election Manifesto Poverty Audit were all motivated by the urge to ensure poverty – in all its complexity - is discussed during this General Election. Having brought together so many academics, activists and committed individuals from a variety of disciplines and interests, we will be taking this agenda forward. Please join us on www.UKPovertyAudit.org.

We welcome feedback on our approach. We hope to develop the design for future audits here and abroad. And we will be tracking the next government’s commitments over its upcoming term.

Please contribute to a public debate on the impact of parties’ policies on poverty and consider the impact of parties’ policies on poverty when you vote on 7th May. With an estimated 13 million people in poverty in the UK, we can't ignore it.

Our Scorecard table of contents shows the final scoring of each party against the effectiveness of their policies to address poverty. A scoring of 1 indicates very low confidence by the authors in the package of measures, and a scoring of 5 indicates a very high level of confidence. These scores were peer-reviewed.

| 1 = Very Low confidence 5 = Very High confidence | Conservative | Greens | Labour | Lib Dems | UKIP |

| TOTAL | 1.7 | 3.9 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 1.4 |

| Crime & Justice | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Disability | 2 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Education | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Employment | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Fiscal policy | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Health | 2 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Housing | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Immigration | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Migration & Security | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Money & Banking | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Social Security | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Sustainability & Environment | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| International aid | Only scoring UK impact | ||||

| Beyond Aid | Only scoring UK impact | ||||

Key: 1 = Very Low confidence, 5 = Very High confidence in party’s policies addressing poverty and enabling a flourishing UK

All four party manifestos discuss some aspect of the criminal justice system, and, in terms of the similarities, the notion of ‘community’ is echoed throughout as a key space within which to deter crime, facilitate restorative justice and wean young adults off welfare benefits.1 But, by focusing singularly on the ‘community’, the manifestos appear to be suggesting that criminal justice policy is principally relevant to relatively poor neighbourhoods. With the exception of the Green Party, none of the parties make any plausible suggestion, some none at all, as to how they can regulate the financial sector better, prevent the manipulation of financial markets and curb the growth of inequality.

From the outset, Labour makes clear that it has a strong commitment to fiscal responsibility and that national finances, like family finances, have to be managed carefully. In his foreword Ed Miliband emphasises the idea of hard-working people, hard work and hard-working families – and this continues throughout the document as Labour asserts itself to be the ‘party of work, family and community’ (p.8). While notions of poverty and inequality are largely absent, the emphasis on risk and on the uncertainties and insecurities that impact on individual, family and community life are a recurring narrative here. For example, in their discussions around law and order, Labour place a strong emphasis on ‘safer communities’ and in particular on a recurring emphasis on the restoration and consolidation of community policing. Neighbourhood crime is to be managed, it suggests, through policing and the introduction of a ‘new statutory Local Policing Commitment’. The Labour Manifesto does not make explicit what this commitment entails. With that said, Labour’s emphasis on policing, community safety and its commitment to ‘nip anti-social behaviour in the bud’ (p. 52) makes this manifesto appear like old wine in new bottles. In 1997, Labour coined the slogan ‘tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’. In their 13 year tenure, the former New Labour government introduced approximately 3,000 new criminal offences that mostly focused on street-level crime (Powell 2008; Hallsworth 2013). These criminal and civil laws brought economically disadvantaged people closer into contact with the criminal justice system than ever before. Young people, the homeless, sex-workers, immigrants, families living in social housing and people with alcohol and substance misuse problems were criminalised under these new offences. What is more, New Labour’s tough approach to criminalizing street-level activity obfuscated its ‘light-touch’ approach to controlling the business and financial sector (Tombs and Whyte 2010, p.16).

The majority of people drawn into the criminal justice system and who are involved with police and law and order agencies come from disadvantaged and impoverished backgrounds. The relationship between inequality and criminal justice has been well established over successive decades but there is a failure on the part of Labour and other major UK parties to recognise this close interrelationship, or that reductions in welfare and other social provisions create the conditions whereby such relationships are reproduced (Croall 2011 and 2015)

Now 17 years later, the Labour Party seems to be offering exactly the same policy as the Blair-led government. With the exception of the proposal to enforce a tax levy on Mansions worth over £2million and on tobacco firms, it is clear that Labour will continue in this ‘light-touch’ approach. The manifesto reads as though the financial crisis never happened. Even the more obviously business-friendly parties, like the Conservatives, propose some policy to ‘crack down on tax evasion and aggressive tax avoidance’ (p.7) and criminalise companies that fail to ‘put in place measures to stop economic crime, such as tax evasion’ (p.11).

The Liberal Democrats and the Green Party appear to offer alternative methods for reducing and deterring crime, whereas Labour and Conservatives merely suggest more innovative ways of criminalising people and creating more prison spaces to lock them in. The Green Party concede that ‘crime cannot be adequately addressed solely in terms of criminal justice and policing policy’ and pledge to design a criminal justice policy that is not ‘imposed from above but needs as far as possible to be a product of a living, democratic community’. As an alternative approach, it places emphasis on tackling the social causes of crime through the ‘democratic community’, wherein criminal behaviour can be adjudicated ‘informally’. A ‘green justice’ would therefore involve greater ‘public participation’.

The Liberal Democrat’s approach to improving the criminal justice system is underpinned by their view that ‘far too many people are simply warehoused in prison’. Specifically, they pledge to offer ‘improved treatment for addiction and mental health problems in prison’, through the development of ‘a specialist drugs court’. Drugs courts, the manifesto suggests, will offer some degree of separation with regards to how drugs-related offences are punished, compared to non-drugs offences. This proposal will be welcomed by drugs action agencies and penal reform campaign groups across the UK as it purports to steer marginal populations away from the criminal justice system. However, the proposal for drugs courts is inconsistent with their proposal for extending powers to criminalise alcohol-related offences as they claim ‘to support the greater use of Local Authority powers and criminal behaviour orders to help communities tackle alcohol-related crime and disorder’. Overall, the Liberal Democrats do offer an innovative and attractive proposal for steering marginalised groups away from the criminal justice system and therefore reduce the prison population; however, the proposal then fails to encompass alcohol-related offences to the same extent as drugs-related offences.

After several years of aggressive punitive policies that have doubled the prison population, there has been no policy that seriously tackles this now normalised approach to punishing offenders through imprisonment. Any notion of 'public participation' and diverting marginalised groups away from prison would require a cultural shift and considerable effort will need to be made to re-frame attitudes and assumptions towards crime and punishment. The Greens and the Liberal Democrats are the only parties of the five that come close to proposing such a shift.

Meanwhile both Labour and Conservative rely on penal populist tactics to win the approval of the general public. The Conservative party takes pride in the knowledge that the Coalition government generated 3,000 more prison spaces than before 2010, ‘while making savings in the prison budget’. But let's not be fooled - the harmful impact of these savings were felt elsewhere. Suicide in prisons has increased by 69% as the purse strings in prisons have tightened and, in the last 10 years, 163 children and young people have died in custody.

Across all four manifestos, there is considerable emphasis on the victim – child abuse, domestic abuse, child and female sex exploitation, the exploitation of migrant workers and so on. Both Labour and Conservatives propose to introduce a new ‘Victims Law’, specifically to ‘strengthen victims’ rights further’ (p.59). But this commitment to victims’ rights is undermined by two important facts. First, the Conservatives claim that they want to ‘scrap the Human Rights Act and curtail the role of the European Court of Human Rights’, and replace it with a ‘British Bill of Rights’ (p.73). Second, the Coalition government, in 2012 stripped citizens of their right to legal aid. This was the death knell for fair and equal access to justice as it ensured that people coming from disadvantaged backgrounds had no recourse to proper legal representation and support. If this record is anything to go by, how can the British Bill of Rights or indeed the ‘Victims Law’ strengthen people’s rights? In its outline of how it can better support victims of crime and violence, Labour proposes to reintroduce legal aid for victims of domestic violence. While this move will be welcomed by many, it is a drop in the ocean as Labour makes no such proposal to reinstate legal aid for all.

Labour proposes to scrap the ‘discredited’ Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) - the main police watchdog. Seen as not fit for purpose by many, the IPCC has repeatedly failed to serve any sense of justice for families and communities. This move chimes well with its commitment to support victims and will be received well by affected communities.

Overall, however, the Labour and Conservative parties are merely offering more of the same. The only parties that appear to offer a fresh approach in policies relating to the criminal justice system are the Liberal Democrats and Green party. The Green Party’s proposal to adopt less aggressive methods for punishing offenders by tackling the ‘social’ causes of crime, and the Liberal Democrats’ proposal to rethink the criminal justice system for people coming from marginalised backgrounds altogether suggest that these parties have the potential to develop a more progressive criminal justice policy.

“Disability” refers to the ways in which people with impairments are additionally disadvantaged by the ways society responds, or fails to respond, to their needs (UPIAS 1976, Shakespeare 2006). In particular, barriers facing disabled people include discrimination (e.g. in employment), lack of access (e.g. in transport or public buildings), and failures of provision (e.g. of social care funding). To flourish, disabled people require action in all sectors to remove barriers and provide the supports needed to lead a good life: health and social care; employment; welfare benefits; education; accessibility of buildings, transport and information. A human rights framework provides an appropriate cross-cutting approach to disability.

The UK Disability Discrimination Act (1995, amended 2005) mandated greater accessibility and outlawed employment discrimination. This, together with direct payments for personal assistance promoting Independent Living, and slow movement towards more inclusive education, as well as with supportive welfare payments such as the Disability Living Allowance and Access to Work made the UK arguably one of the most supportive places in the world to be disabled in the 90s and 00s.

Although the United Kingdom ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2009, and thus has a legal obligation to promote, protect and ensure the human rights of disabled people, the situation has worsened in recent years. For example, the 2010 Equality Act watered down the disability equality duty on public bodies (DDA 2005). Rising numbers claiming out of work benefits meant steady tightening of the remit and assessment process for Incapacity Benefit/Employment Support Allowance (ESA) first under the Labour Government (2008), and then with further eligibility restrictions under the Coalition Government. The Work Capability Assessment was intended to restrict ESA only to the most needy, but over 40% of the people disqualified have been reinstated on appeal (Franklin 2013). The “Bedroom Tax” has disproportionately affected disabled people who may need extra space and/or find it hard to move to smaller but accessible social housing. Despite recent increases in disabled employment, the employment gap between disabled and non-disabled people has barely shifted. Personal budgets have not increased most disabled people’s control over their own lives, and the abolition of the Independent Living Fund means that the support funding available for many disabled people to live independently in their own homes will reduce. Progress towards educational inclusion has halted or even reversed.

The challenges that governments face are mainly about resources, for example to underpin social care spending. Practically, there are problems ensuring that people who should be working do not claim out-of-work benefits: those people who can work need interventions to promote access to work, while those who cannot should be properly supported through the benefit system. There are also ideological obstacles, given that state intervention and regulation is required to enforce e.g. accessibility standards, inclusive schooling, and employment equality. If state spending and state intervention are seen as undesirable, this will limit options to achieve good outcomes for disabled people.

Beginning with health and social care, it is welcome that all the main parties are finally committed to giving mental health equal priority with physical health, and most talk about increasing access to talking therapies. All the parties talk of integrating health and social care. While this may be motivated by the desire to cut costs and remove pressures on the NHS, it should also simplify life for disabled people. Labour mentions personal care plans and the option of personal budgets for older and disabled people. However, so far personal budgets do not seem to have increased control for the majority of disabled people. Labour also commits to recruiting more home care workers. The Liberal Democrats would bring in a replacement for the Independent Living Fund, abolished under the Coalition, while the Greens would retain the Independent Living Fund, as well as increasing funding for social care for disabled adults. UKIP pledges that disabled people will be able to access both domestic, institutional and community support. All of the parties would give extra support to informal carers.

On employment, the Conservatives have pledged to halve the disability employment gap, which would certainly make a difference to thousands of disabled people. However, they have given no details of how they would do this, and as they are also pledged to cutting red tape and social spending it seems implausible that they would act to prevent discrimination by employers or extend the Access to Work scheme. Labour says they will introduce a specialist support programme to ensure that disabled people get more tailored help into work, while the Liberal Democrats will simplify and streamline back-to-work support for disabled people, as well as expanding the Access to Work scheme which supports disabled people with employment costs. The Greens too would promote the Access to Work scheme.

On welfare benefits, disability benefits are exempted from the Conservatives benefit freeze and from their cap on benefits per household. However, the Conservatives do mention potentially cutting welfare benefits for people who refuse treatment for substance dependency or obesity. Labour has pledged to reform the Work Capability Assessment and to abolish the ‘bedroom tax’. The Liberal Democrats would review sanctions processes, “punitive” cuts to benefits, the Work Capability Assessment and Personal Independence Payment assessment to ensure they are fair, accurate and timely, as well as investing to clear the backlog in PIP assessments. They mention integrating different disability benefits, and pledge to ensure that the ‘bedroom tax’ does not penalize disabled people. The Greens would explicitly increase the budget for disability benefits. UKIP would end the Work Capability Assessment and return disability assessments to GPs and NHS specialists, and are committed to a fairer welfare benefit system.

On education, as well as early identification of special educational needs, the Liberal Democrats pledge to promote “local integration of health, care and educational support”, although this seems to fall short of the unequivocal commitment to inclusive education that the disability movement would prefer. Labour would give teachers better training to work with children with special educational needs. Liberal Democrats are pledged to maintaining the Disabled Students Allowance, which has been restricted under the Coalition. The Greens would “recognize the rights of disabled children in education”.

Only the Liberal Democrats say much about accessibility, pledging to make more railway stations accessible, promoting public transport access for people with visual and hearing impairments, outlawing discrimination against disabled people in taxis and minicabs, as well as reforming Blue Badge parking legislation. The Greens would provide disability equality training for taxi drivers.

The Conservatives explicitly mention disability hate crime legislation, although they also intend to abolish the Human Rights Act: it remains to be seen whether their proposed Bill of Rights would ensure rights for disabled people. Labour is pledged to keep the Human Rights Act, and to strengthen the law on disability and other hate crimes. Liberal Democrats too would address disability hate crime, by increasing monitoring, and would fight prejudice and discrimination, for example through fully implementing the Equality Act.

Given that the Conservatives need to save £12 billion (UKIP also accept these figures), Labour £7 billion, Liberal Democrats £3 billion, further restrictions of spending on disabled people cannot be ruled out. Both Labour and the Conservatives mention disability only briefly. However, because Labour have pledged to abolish the “bedroom tax” and reform the Work Capability Assessment, their approach seems likely to do more to reduce the poverty which so many disabled people currently endure. Overall, the Liberal Democrats have the most comprehensive response to disability of all the parties. The Greens also seem to have an explicit commitment to disability rights and full participation in society, and they challenge the need for more austerity. Only the Greens and UKIP mention the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

The goal for education and training policy is to close the attainment gap between wealthier and poorer children, and to provide access to a range of meaningful, well-recognised educational and vocational opportunities for all young people. This requires cohesive policy at all stages in the educational pipeline and for wider issues of social injustice to be systematically and coherently addressed.

Relevant resources need to be equitably distributed, opportunities made available and promoted to all young people, barriers identified and collapsed, and an environment created that enables all to flourish, regardless of background, ethnicity or gender.

An increasingly fragmented educational and training provision poses a challenge to any incoming government. Local Authorities have been weakened by structural changes and ‘choice’ agenda have resulted in disadvantage for some young people. The biggest challenge will be to address the root causes of educational under-achievement, which can be cultural, long-standing and deeply embedded in some communities.

All parties set out a vision for education policy that promises to be inclusive and to address long-standing inequities. However, coherent links with wider social policy are not always evident, and few new initiatives are costed appropriately.

Labour rightly make the point that “every taxpayer pays the cost of low educational achievement” and offer many new ideas: a “Technical Baccalaureate” vocational award for 16 to 18-year-olds; a new ‘Master Teacher’ status; new “Directors of School Standards.” Funding details are generally thin, but it’s noted that “private schools currently benefit from generous state subsidies, including business rates relief worth hundreds of millions of pounds.” In terms of higher education, Labour plans to cut tuition fees from £9,000 to £6,000 a year, funded by restricting tax relief on pension contributions for the highest earners and clamping down on tax avoidance. Who benefits from this cut isn’t clear though. The Institute for Fiscal Studies claims that higher-earning graduates would be the biggest winners. More valuable is Labour’s promise for “a new, independent system of careers advice, offering personalised face-to-face guidance on routes into university and apprenticeships”. This is long overdue and offers the potential to level the employment playing field further.

The LibDems boast of a “record of delivery” as Coalition partners and offer a “promise of more”. Commitments such as that to “end illiteracy and innumeracy by 2025” may remind voters of previous undelivered pre-election pledges, but those from poorer background will welcome the pledge to “give young people aged 16–21 a discount bus pass to cut the cost of travel.” The LibDems will establish an independent Educational Standards Authority (ESA) entirely removed from Ministerial interference and increase the Early Years Pupil Premium – which gives extra money to help children from disadvantaged backgrounds – to £1,000 per pupil per year. Such measures are welcome, targeting those most in need with minimum interference, though full and detailed costings are not always supplied.

The Green agenda is built around the notion of the “common good” and the party’s education policy reflects this. Class sizes would be limited to 20, and there’d be a greater focus on play, social cohesion and confidence building among the under sevens. Curricula would be widened and private schools’ charitable status abolished. All of these measures are progressive and promise to close attainment gaps between socio-economic groups. The Educational Maintenance Allowance is restored and an extra £1.5bn is found annually for Further Education.

The Conservative Party takes a stricter and more traditional approach. They vow to improve primary schools “with zero tolerance for failure”, but little mention is made of trusting the teaching profession to deliver without continued political interference in curriculum. Every “failing and coasting secondary school” will be turned into an academy and there will be “more power over discipline”. The language of competition (not co-operation) dominates, with an increase promised in the number of teachers able to teach Mandarin in schools in England, “so we can compete in the global race”. Universities will focus on ‘value for money’ and will be required to offer more two-year courses.

UKIP plans to maintain selective systems in secondary school and will introduce a 12+, 13+ and 16+ exam to complement the 11+ exam. UK students taking approved degrees in Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics and Medicine (STEMM) will not have to repay their tuition fees. Like other parties, UKIP aims to “improve social mobility for able children from poorer backgrounds,” but few specific measures are offered beside the ubiquitous promise of a “grammar school in every town”.

When it comes to Education and Training, the main parties’ manifestos are alike in some ways. Many acknowledge the decreasing influence and autonomy of local authorities and, indeed, of individual teachers in education administration. But the manifestos also differ in key ways. For example, while most include promises to reduce class-size, improve teacher skills and expand vocational opportunities, the Greens seem to have an especially strong focus on making college affordable and the LibDems on evidence-based social and family support for disadvantaged children in early ages. Labour presents a persuasive narrative about raising educational achievement among the most marginalised groups. The challenge for whichever party (or parties) succeed in winning power will be to deliver on their manifesto principles, even if policy compromises are needed, and to give more children the resources they need to move away from poverty, reach their full educational potential, and maximise their personal wellbeing.

Sen’s Capability Approach has been applied to the topic of work by others (e.g. Salais, 2003; Salais and Villeneuve, 2004; Bonvin, 2008; Bonvin and Farvaque, 2006; Zimmerman, 2006; Orton, 2011) to examine how it might be applied to paid employment in Western countries. Such an approach sees employment as key in relation to needs at both an individual and societal level e.g. providing income but also potential for identity, recognition, learning, creativity, and contribution to wider social goals, and contrasts this with current neo-liberal orthodoxies which are ascribed as the cause of the UK’s well-rehearsed list of problems such as low wages, zero hours contracts, the gender pay gap, other aspects of discrimination, and so on.

Employment covers a very wide range of issues but in seeking to redress problems within the realities of the current UK labour market and frame employment positively in terms of a Capability Approach with a goal of enabling flourishing lives, six objective criteria are as follows,

So is there evidence of these criteria being addressed in the Party manifestos? Considerable prominence is certainly given to employment e.g. Labour says its manifesto is “a plan to reward hard work” while the Conservatives declare “Jobs for All” (the exception is UKIP’s manifesto which in a short section frames employment problems and solutions within EU membership and does not meet any of the six criteria). The downside to the general emphasis on employment is a failure in relation to criterion 6 i.e. recognition that paid employment is only one element of human activity. There is near complete omission of this and sparse mentions are not supported by realistic policy measures e.g. the Conservative manifesto says “We will support you, whether you choose to go out to work or stay at home to raise your children” but policy is highly partial, based on transfer of married couples’ tax allowances. The Green Party proposal for potentially far greater change through a Basic Income is referred to only as a long-term ambition. The stronger sense is of what Levitas (1996, 12) argued to be the case twenty years ago: “The possibility of integration into society through any institution other than the labour market has disappeared”. The other five criteria will now be considered in turn.

Living Wage – There are many promises to increase (net) wages but whether sufficient to provide a true Living Wage is less clear. The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats propose further increasing the Income Tax threshold. Labour’s emphasis is on reducing the starting rate of Income Tax, increasing the National Minimum Wage (NMW) and incentives for employers to pay the Living Wage. Green policy is similar to Labour but with more rapid increases to the NMW. The Conservative-Lib Dem approach of the last five years has been unsuccessful in redressing low wages and more of the same seems unlikely to do so. Increases to the NMW are certainly positive but whether a Living Wage can be achieved through incentives to employers remains to be seen.

Good work – Aspects of the notion of Good Work feature in the manifestos but there is again a potential gap between stated aspirations and policy development to achieve those aspirations. For example, the Conservative manifesto does recognise exploitation but elides this with illegal working and illegal immigrants. In relation to voice, the Conservatives propose more restrictions on trade unions. Labour and the Greens (and to some extent the Liberal Democrats) propose tackling elements of zero hours contracts, unpaid internships and are positive about the role of unions. There is also a difference of emphasis between the Conservative and Labour manifestos with the former arguing for less regulation of employers while Labour does link change by employers and better quality employment. While individual measures may help towards creating Good Work the overall sense across the manifestos is, however, of far greater emphasis on claims of how many jobs different parties will create - the nature of those jobs does appear as a secondary rather than integral concern.

Prioritise equality – The Greens place strong emphasis on equality and diversity across policy domains including employment, but in other manifestos it is the theme of a gap between stated aspirations and realistic policy development that is most evident. For example, the Conservative manifesto states “We want to see full, genuine gender equality…we want to reduce it [the gender pay gap] further and will push business to do so: we will require companies with more than 250 employees to publish the difference between the average pay of their male and female employees”. The Liberal Democrats and Labour make more substantive pledges than this, but to a lesser extent than the Greens. The priority given to equality is a definite difference between the manifestos with the Green Party manifesto clearly scoring highest in presenting equalities as a core concern.

Employability and job creation – Various claims are made in the manifestos about how many jobs will be created by the different parties but, as with the above separation of job creation and Good Work, so job creation and employability measures for those not currently in work are presented as different policy domains. While in the main described as ‘support’ for helping people into work, such support is not linked to the availability and suitability of job opportunities. Much focus is on young people, but there is little evidence of a Capability Approach based on ensuring opportunities and choice. It is coerciveness that is far more evident, for example captured in this from the Labour manifesto: “There will be a guaranteed, paid job for all young people who have been out of work for one year, and for all those over 25 years old and out of work for two years. It will be a job that they have to take, or lose their benefits” or from the Conservatives: “We will replace the Jobseeker’s Allowance for 18-21 year-olds with a Youth Allowance that will be time-limited to six months, after which young people will have to take an apprenticeship, a traineeship or do daily community work for their benefits”.

Linking paid employment to sustainability – Unsurprisingly, the creation of green Jobs features strongly in the Green manifesto but Labour too pledges to “make Britain a world leader in low carbon technologies over the next decade, creating a million additional green jobs” with a “Green Investment Bank to be given additional powers so that it can invest in green businesses and technology”. But here again there is a separation between creating (green) jobs and the nature of those jobs, with far greater emphasis on the former over the latter.

In summary, taking the manifestos as a whole there are aspirations and individual policies which potentially chime with aspects of a Capability Approach but they do so only in a piecemeal and coincidental way. There are certainly differences between the manifestos. At a theoretical level the Greens reject neo-liberalism, although they are the only Party to do so, and aspire to a very different political economy. At a policy level, the Conservative and Labour manifestos point to elements of variance if either forms a government. But to follow a Capability Approach would require adopting the theoretical development by Salais, Bonvin and others, and addressing the six criteria above in the round, seeing them as mutually-reinforcing and creating an upward virtuous cycle. This is not the case in any of the manifestos and while some positive changes to employment policy are promised, these do not offer the transformative potential of a Capability Approach nor a sound basis for the opportunities, choice and freedom central to such an approach's role in enabling flourishing lives.

The structure of public expenditure and taxation has implications for a flourishing life. Fiscal policy relates to the intended balance between government expenditure and tax revenues. It is a policy tool to influence the level of demand (and therefore employment) in the economy. The main impact of fiscal policy comes through its ability (or otherwise) to secure full utilisation of resources, notably employment. A good social outcome is where fiscal policy is used to enhance employment and economic activity rather than to meet an arbitrary budget deficit position.

Fiscal policy and the scale of and change in the budget deficit/surplus, is normally framed as a national target without due consideration for equity dimensions. It is generally the case that the desirability (or inevitability of) an arbitrary budget position is asserted without any rationale being given.

Reducing the budget deficit is currently a key focus of fiscal policy in the UK. There are three ways this can take place - cuts in public expenditure, increases in tax rates, and increased tax revenues (and some reduction in unemployment related payments) as growth occurs. Four key criteria apply when assessing budget deficit targets:

From the above, it is clear that whether budget deficit targets are reached depends not only on expenditure and tax rate decisions but also on the level and structure of economic activity. A further consideration is whether fears of deficit and debt militate against public investment at a time when borrowing costs are low and there is evident need for such investment.

Reducing the budget deficit also requires assumptions to be made about the future. One major issue is that the outcome is not under the control of government but dependent on the level and composition of economic activity. Specifically if investment and net exports do not grow substantially then the budget deficit will not decline as intended.

A challenge for parties that seek to dramatically reduce public expenditure and/or particular elements is the social acceptability of such changes. The ability of parties to deliver on their deficit pledges will also depend on support from their peers in Parliament across the political spectrum. Each of the five parties has programmes to reduce the budget deficit over the next five years. A brief summary is below.

| Conservative | Budget deficit eliminated by expenditure cuts in first two years of 1 per cent per annum; achievement of overall budget surplus by 2018/19; and declining debt to GDP ratio; public expenditure growth in line with |

| Labour | Budget deficit on current spending to be eliminated ‘as soon as possible’; ‘no new proposals for spending paid by additional borrowing’; allow borrowing for investment purposes. |

| Liberal Democratic | ‘Structural current budget’ deficit eliminated by 2017/18; ‘over the cycle balance the overall budget’ but ‘borrow for capital expenditure that enhances economic growth or financial stability’ |

| Green Party | Substantial increases in public expenditure, development of new taxes: spending 45.1 per cent of GDP (compared with Coalition plans of 36.0 per cent), tax revenues 44.0 per cent (36.3 per cent); achieving a surplus on current budget of 2.7 per cent of GDP by 2019, and with 3.7 per cent of GDP spent on public investment, an overall deficit of 1.0 per cent. |

| UKIP | Accept the budget deficit proposals of the Coalition government (March 2015 budget) and ‘eliminate deficit by third year of Parliament’, and then surplus, ‘holding the Chancellor’s feet to the fire’ to reduce deficit. Own plans for changes to tax and spending are put at around £32 billion in each case, hence no overall effect on budget deficit. |

Overall, Conservative, UKIP and Liberal Democrats share the position of eliminating the overall budget deficit, whereas Labour, Green and SNP aim more for a current budget balance with borrowing for investment (a return to the ‘golden rule’). The Green Party has on the surface somewhat more fiscal tightening than Labour Party, but in the context where expenditure and tax revenues would be some 8 to 9 per cent of GDP higher.

One consequence of the above is the level of debt to GDP. This is decried by some (including Liberal Democrats and UKIP) as impoverishing our grandchildren. However, the reality is that the national debt (government bonds) forms an asset for people which can be passed on to their grandchildren.

The parties do not discuss what effect their expenditure and tax plans will have on employment and output. Insofar as the expenditure and tax revenue changes are set out in any degree of detail (as they are in the Green Party manifesto) then it is against a background of a given set of forecasts for output.

There is also a lack of distinction between a balance of the total government budget and a balance of the current budget. This difference is equal to the scale of public investment, and could amount to the order of 2 per cent of GDP. Such a difference in the level of expenditure would make a significant difference to the levels of output and employment.

Manifestos lack the detail to make comparisons between the composition of the spending and tax plans and the effects it will have on a ‘flourishing life’. Nonetheless, we can offer the following insights.

A key concern for the public should be the scant information as to how parties will respond to failures to meet specified deficit targets. Such failures are virtually inevitable as parties have put forward different targets underpinned by different assumptions; and the complex of interplay of these assumptions and their validity has not been sufficiently explored.

Health is a major campaign focus in the General Election 2015 due to critical media attention on weak hospital performance and missed waiting list targets, as well as widespread public perception of creeping privatization in the NHS. It may also be a decisive one, since the main political parties’ manifestos reveal some fundamental differences in their health programmes. Even at first glance, variation in the prioritization of this policy area, as read from its position and attention to detail in the manifestos, is noteworthy: the Liberal Democrats dedicate an entire 14-page chapter to a ‘healthier society’ and the Greens’ present their thorough five pages of text on ‘health and well-being’ relatively early on in their document, whereas both the Labour and Conservative parties have chosen to combine their health and education contributions into single chapters. The Conservatives’ title for this chapter is one that headlines hospitals, which indicates that their perspective prioritizes these institutions over community-based or preventative care, and its three-page sub-section on health is focused specifically on the NHS, rather than health more generally. Likewise, the UKIP manifesto offers three pages of text on the NHS expressly, though these appear relatively early on in the document and are followed by a separate (page long) chapter on social care.

These introductory observations prompt questions around what should or could be included in the parties’ manifestos on health. The challenge here is to do with the breadth and depth of this policy area – since the meaning of good health has long superseded the simple notion of being free from illness and now embraces a wider sense of wellbeing. A good social outcome in this area means a more pervasive health and happiness, an ability to live with and manage any long-term conditions, as well as the means to maintain wellness through all stages of life. To be well, on this view, is a holistic matter, with emphasis being placed upon the prevention of poor health – from imbalance diets to imbalanced work and social lives – by both informed individuals and carers. In a developed world context, moreover, high-quality solutions to health problems should be readily and equitably available as well as compassionately delivered.

To what extent can or will the main political parties recognize and act on this scale? The Green Party manifesto stands out in its appreciation of the factors that contribute towards good health: its chapter’s opening statement sets out a vision of well-being based on satisfying work and a balanced diet alongside good housing, education and transport as well as greater equality. It recognizes different segments of society, most explicitly in its sub-section on mental health, though there is particular emphasis at the very early and late stages in life, which is not unique to the Greens. What is unique, is the extent to which they take their stance against privatization of the NHS: they will not only repeal the Health and Social Care Act (HSCA) 2012 but abolish the purchaser-provider split (which dates back to 1990 and is, arguably, the defining feature which mimics the market within the NHS).

Both the Labour Party and Liberal Democrats take a similarly system-wide view of healthcare, relative to the Conservative Party and UKIP, and have also decided to repeal the HSCA 2012. That said, the Lib Dems restrict this reform only to the Act’s parts that render the NHS ‘vulnerable to forced privatisation’. And Labour conflates its repeal with the ‘scrapping of the competition regime’, without adequate recognition or management of the market features embedded in the NHS that precede that Act. None of the three parties committed to this repeal provide sufficient detail about the future of the commissioning structures, the Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), established under the HSCA 2012. UKIP, in contrast, indicate that they have decided against this course of action so as not to waste resources on further re-organization and instead focus on policies to restrict ‘health tourism’ and scrap hospital car parking charges.

Without commenting upon whether the so-called privatisation of the NHS is a legitimate public concern, the political parties’ reflections at this level demonstrate the broader need to think beyond certain issues like specific hospital provision. It is in this vein that transformative work around preventative care can happen, contributing squarely towards a person’s ability to flourish. Apart from UKIP, which makes no reference to preventative care, all the other main political parties include in their manifestos policies to encourage individuals to make better lifestyle choices (e.g. minimum pricing for alcohol, regulation of junk food advertising). In fact, both the Greens and the Lib Dems go further, matching this personal responsibility with governmental responsibility to control air pollution, something that is responsible for thousands of premature deaths in the UK each year.

Moving from preventative care to specific clinical foci, two areas have received particular attention, to varying degrees, in the main political parties’ manifestos: mental health and care for the elderly. The Conservatives include a paragraph on each, and the Labour Party includes a paragraph on the former together with a section on the latter that proposes the ending of 15-minute care appointments. The majority of UKIP’s short chapter on social care is dedicated to older people and they propose to finance this through a Sovereign Wealth Fund gained form shale oil and gas exploration (fracking). In contrast to this, the Greens and Liberal Democrats include whole sub-sections focused on mental health in their manifestos. They each lean towards different segments of society – the Lib Dems to prevention and management for young people, and the Greens to diverse groups (mothers and children, BME and LGBTIQ communities as well as refugees and ex-service people) – but both are thorough and connect the dots between wellbeing and secure, balanced employment.

This linkage is mirrored in two headline issues that are intertwined and also impact upon the compassionate delivery of healthcare: access to services and our health and social care workforce. All the major parties are pledging greater access to healthcare services, be it through GP services running 7 days a week, or guaranteed appointments in, typically, 48 hours. But these pledges are supported by funding figures that are insufficiently detailed from source to implementation – only the Green Party and UKIP attempt a financial breakdown for their whole manifestos (the former being significantly more detailed than the latter). There is inadequate attention paid to how GPs will be persuaded to do this, particularly at a time when great swathes of the profession feel excessively burdened already and there is a critical shortfall of replacements. The minority parties – the Greens, Lib Dems and UKIP – come closest to recognising the healthcare workforce as a vulnerable group, and to making tentative links between their value (financially and otherwise) and their ability to deliver high-quality care compassionately. This is fundamental to the sustainability of the NHS.

What is clear and critical for any contemporary campaign relating to health, in a developed world context such as our own, is the interconnectedness of policies beyond hospitals and specific clinical interventions to whole structural programmes. Labour’s manifesto section on health lacks detail and bite, whilst UKIP is too focused on minor concerns and the Conservatives’ bears the hallmark of an incumbent player. Conclusively, the Greens and Liberal Democrats manifesto offerings in healthcare most enable a person and community to flourish, though they are significantly divided by a fundamental point on the structure of the NHS – a decisive point for voters.

It is widely recognised that the aim of housing policy should be to provide a decent quality home at a price that can be afforded with sufficient choice over property size and tenure to meet the increasing diversity of household circumstances. These challenges have sometimes been condensed into the 3 As - of adequacy, access and affordability. One might wish to add 'security' to this list. Housing policy also needs to respond to the growing local sub-regional and regional disparities that are intensifying in the housing market. Much of the challenge for policy revolves around the widespread accceptance that housing supply has not kept pace with growing demand, especially in the past ten years, given growing net migration and changing patterns of household formation. The suggested ways of tackling the housing shortage naturally vary according to political outlook. Advocates of the free market approach suggest that the removal of planning restrictions will encourage private developers to build more properties than before. Critics of this approach argue that it would intensify spatial inequalities and that housing supply has only been radically increased in previous decades where there has been a significant investment in new social housing as well, financed through borrowing.

In terms of the parameters shaping the achievement of good social outcomes in housing, the issue of resources requires sufficient investment to be made in new building and in the renovation of existing dwellings to ensure decent housing through the generations, not just a 'quick fix' of speculative building in response to a specific short-term policy incentive. The aim of a balanced housing market will provide more opportunities for households to move in accordance with their needs (family links, employment, changes in household size, life stage) and not to be forced out of unaffordable localities so they are displaced and lose out in terms of maintaining close social networks and access to key services such as schools. The barriers to balanced housing markets include high costs, poor standards of design, construction, management and maintenance, and a discrepancy locally between options to rent or to own. The enablers should be to provide sufficient security and stability so the home can be an anchor to an active and fulfilling social, personal and working life. 'The home should be the base for your adventures, not an adventure in itself.' (Aneurin Bevan, 1952)

The way to achieve more equitable housing outcomes is through public stimulus to supply, especially in areas where households face the most acute affordability problems, coupled with a tighter regulatory regime on the growing private rented sector where standards of property condition, management and maintenance are variable, and often extremely poor for more vulnerable households. This approach involves redirecting public expenditure away from financing housing consumption, through the annual £23 billion Housing Benefit bill and the Help to Buy initiative, and to redirect it to housing production, to bring down costs at source. It may also require controls over private developers, where profitability levels have been increasing far faster than output since 2010. The challenge then becomes how to achieve increased building while ensuring both new and existing properties achieve higher standards of space, warmth, insulation and energy efficiency, using sustainable materials wherever possible.

One of the major challenges for any housing programme is how to match a relatively inflexible form of supply - a built dwelling - to often quite rapidly changing trends in household circumstances, resources and preferences. The major party manifestos all fail to respond adequately to this diversity. The main parties, especially the Conservatives, are mesmerised by the fate of the thwarted first time buyer.

The Conservatives bring forth a raft of proposed measures - a Help to Buy programme, a starter homes programme, a rent to buy programme, a new Help to Buy ISA and above all the extension of the Right to Buy to 1.3 million housing association tenants. This is an obvious attempt to recreate the political dividend of the original Right to Buy offer to council tenants. But housing circumstances have changed in the past thirty five years and the impact of the policy may be much less marked in the housing association sector. Housing associations are legally constituted - as Community Benefit Organisations - in a different way to local authorities. Entry into home ownership - even nurtured by large discounts - is seen as a more hazardous option than it was, and those long-standing housing association tenants who stand to gain most are less likely to be in work and have more diverse demographic attributes (and, perhaps, voting preferences) than the council tenants of the 1980s.

Overall, the above measures are likely to do little to increase overall housing supply. Speculative developers may not necessarily build more, but simply swap unsubsidised housing schemes for subsidised schemes. Private developers, concerned solely with making the first sale, will often play safe in terms of the envisaged purchaser - hence the preference to build for the first time buyer or those who are trading up. More diverse needs may be neglected. This may include single people of all ages, those on low incomes who can barely afford to rent, let alone buy, and marginal and vulnerable groups who have been hit by welfare reform measures affecting their access to, and the level of, their benefits.

There is no mention in any of the manifestos of the main parties about the specific challenges facing members of black and minority ethnic communities in local housing markets, nor those who face discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. The Green Party's manifesto, however, does devote a specific chapter to Equalities and this contains reference to some housing proposals.

It is especially notable that so little is said about the need for a regionally differentiated housing programme, given the diversity of housing market issues. In the London areas, spiralling housing costs in all sectors overshadow all other concerns, as well as some of the consequences for the use of temporary accommodation, and levels of statutory and hidden homelessness. These affordability pressures for poorer households have been intensified as a result of the various welfare reform measures introduced since 2010. However, in other parts of the country, more pressing issues concern the poor standard of private rented properties at the lower end of the market, the need to revive local regeneration programmes abandoned since 2010. These issues are generally overlooked in the manifestos.

Compared to the Conservative offer, the LabourParty has a more balanced programme of new build between renting and buying, though they also advocate a Future Homes Fund to help young people and families. The Labour Party, UKIP and Greens are all committed to abolishing the Bedroom Tax, widely seen as inequitable. However the need to respond to the reductions in Housing Benefit in the private rented sector, which amount to six times the reductions caused by the Bedroom Tax, only occasion comment comes from the Greens.

One under-used resource in the housing system is homes of more affluent older owner-occupiers, under-occupying to a far greater extent than those council tenants who were the focus of the Bedroom Tax. There is silence on how some of these assets might be unlocked through imaginative equity release schemes, for other generations and household types. However, Liberal Democrats, Greens and UKIP all mention restoring empty dwelling to occupancy as a priority.

The rise of 'generation rent', whereby the proportion of households aged between 25 to 34 in the private rented sector has risen from 21 per cent to 48 per cent in the ten years from 2003/4, is noted by all parties. Conservatives reject more regulation, while 'encouraging' landlords to offer longer term tenancies. Labour proposes to make three year tenancies the norm, place a ceiling on rent rises banning agents from charging fees to tenants and introducing a 'national register' of landlords.

Other issues that could affect the functioning and affordability of the housing market do not make it on to the parties' manifestos including land taxation - suggested by the Liberal Democrats in 2013, but now dropped.

The most far-sighted and radical proposals for housing are advocated by the Greens in addressing what many analysts identify as some of the long standing structural peculiarities of the British housing market - over-emphasis on owner-occupation, serious lack of investment in social housing, an inefficient, expensive and ill targeted housing benefit regime, and an unduly permissive regime for the private rented sector. The proposals include: ending the right-to-buy and replacing it with a right-to-rent policy; scrapping mortgage interest relief for buy-to-let mortgage holders; capping rent rises at the rate of inflation and establish a Living Rent Commission; building 500,000 new socially rented homes by 2020; abandoning the classification of intentional homelessness by local authorities; ending the use of hostel and B and B provision for homeless households; promoting housing co-operatives and self-build schemes; phasing out assured tenancies; and applying new standards for accessibility, space and facilities insulation and energy efficiency.

At the other end of the spectrum, potentially the most socially divisive policy is the proposal by UKIP that a 'test' of local priority for social housing will be made, that will depend on a parent or grandparent being born in the area. They suggest that the right to buy and help to buy would be removed from foreign nationals, except those who have served in the armed forces. One might wish to ponder how far that will really get to the root of the country's housing crisis.

There are three interconnected social outcomes. The first is achieving equality of entry, permitting immigration on an equal basis regardless of socio-economic status. This would support human flourishing internationally, as favouring immigration of only the wealthiest risks deepening international poverty. It also drives undocumented immigration of the most desperate, which underpins enduring labour exploitation and social exclusion (Goldring and Landolt 2011). The second outcome is reducing the ‘precariousness’ of immigrants living in the UK (Anderson 2010) by ending this exploitation as well as the constant threat of destitution, detention and deportation (Allsop et al. 2014), and by ensuring that migrants have access to adequate social security. The final outcome is for migrants to be respected as members of society and not just as commodities of the international labour market, allowing them to flourish as co-members of society and through rich social and family ties (Sigona 2012; Tonkiss 2013).

To achieve these outcomes, the next government will need to overhaul immigration policy to ensure equality of entry, to reduce the precariousness that migrants experience once they have arrived, and to support migrants to flourish in the communities in which they live. The key barrier that they will face in achieving this is the widespread hostility towards migrants currently experienced in the UK. While the next government will face challenges in the provision of public services, migration itself brings net benefit to the welfare state (Vargas-Silva 2015) and therefore welfare state concerns should not act as a barrier to these outcomes.

It is UKIP whose proposals will have the worst outcomes for migrants. UKIP intends to stop all unskilled migration for five years, including from within the EU. While UKIP claims that this will help unemployed British people find work and will increase wages, in reality migrants are filling gaps in labour markets and as such banning unskilled migration will have detrimental effects on local economies, with resulting social costs. This policy also risks deepening international inequalities by prioritising only highly skilled (and therefore likely wealthy) migrants through a points-based system, and leaving existing migrants vulnerable to exploitation as a result of the threat of detention and deportation. UKIP will also prevent migrants from accessing social security benefits, including non-urgent healthcare, until they have worked in the UK for five years. This will compromise the ability of migrants earning less than the living wage to support themselves and their families and to maintain adequate physical and mental health. It will also leave them at risk of destitution and homelessness.

The Conservative Party manifesto offers a similarly tough stance on migrants’ access to social welfare. Under the proposals, migrants will not be able to claim tax credits or child benefit, or live in a council house, until they have worked in the UK for four years. They will also only have six months in which to find another job should they become unemployed before they are deported, and these proposals will apply to both EU and non-EU migrants. These policies again undermine the ability of migrants who are making significant contributions to the UK economy to support themselves and their families, to find affordable housing, and to live without the threat of deportation and destitution. Like UKIP, the Conservative Party wants to drastically cut low skilled migration and this will bring the same problems as noted above. Their plans to ‘deport first, appeal later’ regardless of family situation also mean that the threat of deportation could extend to those who have lived in the UK for decades. However, the Conservatives do offer commitments to tackling the exploitation of migrant workers, which is to be welcomed.

The Labour Party similarly plans to introduce rules to prevent the exploitation of migrant workers, and also introduce commitments to end the indefinite detention of immigrants and asylum seekers together with a liberal approach to accepting refugees. These proposals have the potential for positive impact on migration-related poverty, allowing migrants to find stable lives in UK communities rather than being held in detention centres or trapped in refugee camps. However, Labour also emphasises high skilled migration over low skilled migration, again meaning that it will be predominantly wealthier people who benefit from migration, and propose that migrants will not be able to claim benefits for two years, which will have severe implications for those in low paid employment.

The Liberal Democrats’ plans focus less on access to welfare, although there are plans contained in their manifesto to make access to Job Seekers’ Allowance dependent on the ability to speak English. Similarly to Labour and the Conservatives, the Liberal Democrats intend to work to prevent labour market exploitation, but they are also keen to see asylum seekers able to find employment should their asylum applications be taking too long. Alongside this proposal, their plan to abolish the Azure card which prevents asylum seekers from receiving cash and a result limits their freedom to choose how to live their lives, is to be welcomed. The Liberal Democrats will also work with European countries to address migration in the Mediterranean, which is critical from the perspective of international flourishing when considering recent high profile migration-related tragedies in this region.

The Green Party offers the most positive proposals for immigration. They intend to pursue a liberal immigration policy which embraces family migration in addition to working age migration, and includes the migration of adult dependents which will enable migrants to build rich social and family lives. The Green Party also emphasises equality of entry for migrants regardless of their economic value or personal wealth, which will also reduce international poverty. The Greens are committed to ending immigrant detention, and will also offer an amnesty to undocumented migrants in order to avoid destitution. This is likely to reduce the precariousness that migrants experience. Furthermore, the Greens will go further to tackle migrant exploitation than other parties, proposing to ratify the International Labour Organisation’s Domestic Workers’ Convention which will address the exploitation of vulnerable domestic migrant workers in the UK.

In summary, the Green Party offers the best chance of reducing migration-related poverty, while the Liberal Democrats also offer many positive policy commitments. Labour’s approach is less likely to improve the lives of migrants in the UK, while the proposals of the Conservatives and UKIP are likely to exacerbate migration-related poverty.

There are multiple perceptions and understandings of migration and security. Some of them are rooted in evidence and experience, while others are driven by fear and misperception. Regardless of which party or coalition forms the next government, the election will have been valuable if it promotes a serious debate about migration and security in the UK context.

At present, migration tends to be conflated with immigration: as an election issue it is those coming into the UK rather than those who leave that provide the focus of attention. To deal with this issue effectively, policymakers must address its connection to wider economic and social policy, and also look at ways in which inward immigration can contribute to security over the long run. Internationally, the UK must also take action to reduce the likelihood of extremism and violence by targeting pernicious forms of political and economic inequality that often manifest themselves in these ways.1 To be truly sustainable, security in the context of migration needs to address the underlying causes of instability and see security as a collective and ongoing endeavour. In this regard, a narrow focus on physical and territorial aspects of security, as represented by border control agencies, surveillance and response to threat, is often unhelpful.

Together we need to move away from the idea that migration is a matter of control, borders costs, and impact on national identity, and toward a more realistic understanding of the way in which social, economic and political goals can be achieved. Unfortunately, media representation of this issue and political pressure to reduce the deficit, have reduced the amount of space that is needed to engage with security and immigration in a productive way.

A major challenge for the next government will be to reframe the debate on migration and security, moving it away from a populist agenda driven by fear and xenophobia. Currently, the main parties have pledged to control the numbers of migrants coming into the UK and to establish new mechanisms of border control that will ensure that visitors to the UK are closely monitored. Often, immigration will be explicitly linked to schemes that promote de-radicalisation.

Starting first with the major parties, Labour provides a mixed message to potential immigrants, claiming they are valued on the one hand but combining this with a raft of new restrictions. For example, they write that ‘Britain has seen historically high levels of immigration in recent years, including low-skilled migration, which has given rise to public anxiety about its effects on wages, on our public services, and on our shared way of life... the system needs to be controlled and managed so that it is fair' (p.49). Worryingly, the manifesto does not say what it means by low-skilled migration, or state what it sees as fair. Indeed, Labour fail even to state what levels of immigration (from the EU and beyond) they regard as being optimal for Britain. Beyond this, Labour draws an explicit connection between immigration, security and control mechanisms, within a context of a territorially defined containment strategy. They write that, 'Labour’s plan starts with stronger borders. We will recruit an additional 1,000 borders staff… We will introduce stronger controls to prevent those who have committed serious crimes coming to Britain, and to deport those who commit crimes while they are here’ (p.50).

The Conservative Party is more strident about immigration in tone but they differ from Labour only in scale of what they propose rather than in how migration and security are conceived. Together with UKIP they tend to conflate immigration, economic pressure (on the NHS and welfare budgets) and EU membership. They write that ‘we will negotiate new rules with the EU, so that people will have to be earning here for a number of years before they can claim benefits, including the tax credits that top up low wages.’ (p.29). The background to all this, is the problematic idea that migration functions as a drain on UK economy, something that can be seen when they write ‘we have already banned housing benefit for EU jobseekers, and restricted other benefits, including Jobseeker's Allowance. We will insist that EU migrants who want to claim tax credits and child benefit must live here and contribute to our country for a minimum of four years.’ (p.30)

The Green Party comes closest to tacking the themes of migration from a sustainable security point of view. There is an understanding of the links between violent extremism and the political structures within which it is created. They also acknowledge that strong borders, surveillance and militarisation will not be enough for real security over a longer timeframe. Indeed, the Greens draw an explicit connection between UK military intervention in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya ‘and the increased terrorist threat closer to home’ (p.70). The framing of migration is much more positive than that of the other parties. It is seen as a longstanding and natural fact of life that has enriched the UK’s in terms of language, culture and the British way of life over hundreds of years. The Greens write that ‘we live in an interconnected world, which brings huge benefits as well as drawbacks. Decisions that we make affect people in other countries and events in other countries affect us.’ (p68). Here, security is understood correctly as a collective endeavour.