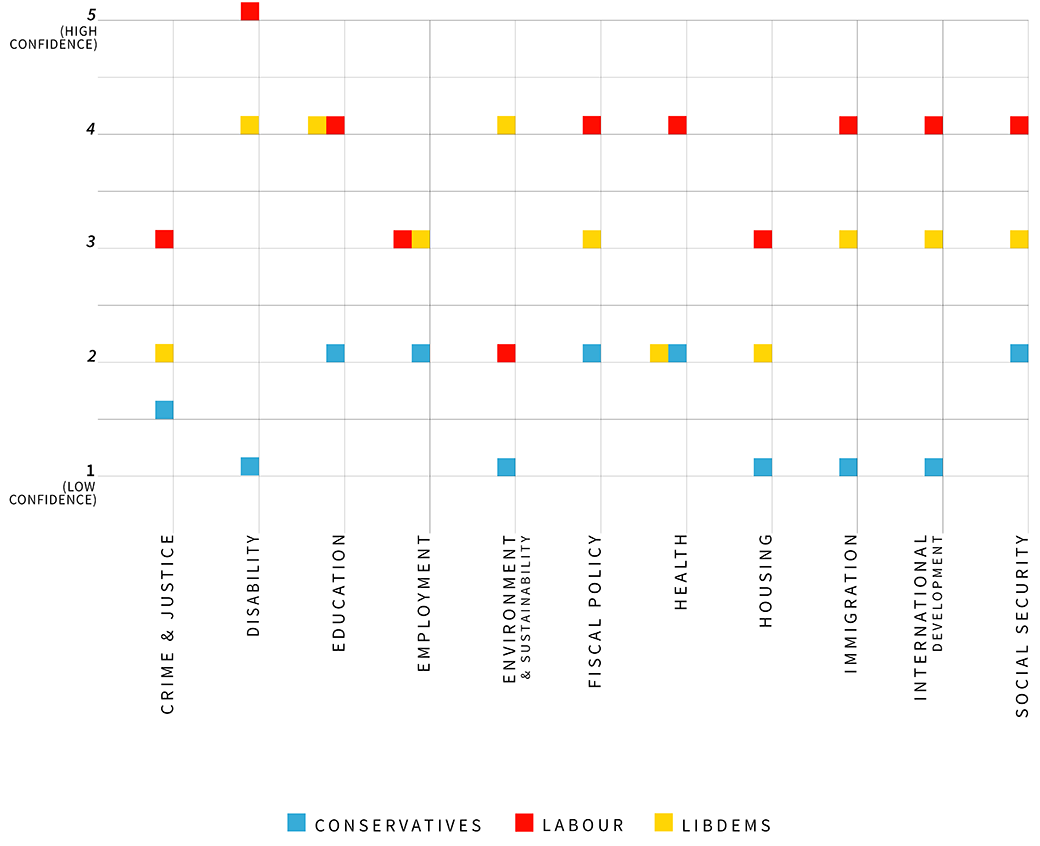

Our Scorecard infographic shows the final scoring of each party against the effectiveness of their policies to enable British society to flourish. A scoring of 1 indicates very low confidence by the authors in the package of measures, and a scoring of 5 indicates a very high level of confidence. These scores were peer-reviewed

Illustrations, infographic and publication layout by Ariadne Radi Cor: http://chantillycream.co.uk

Help spread the word and discuss our findings by following us on Twitter at @academicstanduk and @AcademicsStand and tweet using the hashtag #StandAgainstPoverty. Share it with friends, family and colleagues and make a stand today.

This is a project convened by the UK chapter of Academics Stand Against Poverty (ASAP), an international association focused on helping researchers and teachers enhance their impact on poverty.

Film production by Chris King: http://www.chriskingphotography.com/

There is very little detail about any of the three parties' proposed approaches to Brexit in the manifestos, despite how important an issue this is deemed to be for the election. One particular issue that no parties have given due consideration to in the manifestos is how they will maintain the need to implement their policy priorities - whilst vast civil service resources are drawn into the challenge of implementing Brexit. No scores were given for this chapter.

No party scored higher than Labour’s “medium confidence” for Crime and Justice, with the Conservatives scoring just above “very low confidence”. Both the Conservatives and the Lib Dems advocate a punitive approach to offenders, despite evidence that offering the opportunity to receive education, support, and guidance is likely to be more successful. Labour demonstrate a commitment to the poor and disadvantaged, but still avoids explicitly declaring support for offenders as well as punishment.

The only score of 5 (or “high confidence”) across this audit was given to Labour for their Disability policies. The Lib Dems also did well, scoring 4, whist the Conservatives were given the lowest possible score. In 2016, the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities found “grave or systematic violations” of disabled people’s rights in Britain, and the Conservative policies do not inspire confidence that this is likely to change. Labour promise to abolish Personal Independence Tests and "punitive sanctions".

Labour and the Lib Dems both score 4 for education, whilst the Conservatives receive a 2. Both Labour and the Lib Dems would stop free schools, academies, and grammar schools. The Conservatives are sticking to their policies on these, and would remove the ban on selective admissions, despite evidence that selection in schools has been found to disadvantage those not selected, and children from poorer families are significantly less likely to get in.

The three parties have the lowest disparity in scores in Employment, with Labour and the Lib Dems both scoring 3, and the Conservatives scoring 2. Considerable attention is paid to employment and workers rights in all the manifestos. All parties talk about the importance of “good work”, but the Conservatives mainly describe this in terms of pay levels and job security, while the other parties also focus on job quality and the importance of fulfilling work.

This is the one area where the Lib Dems stand out above the other two parties, scoring 4, and Labour gets its lowest score across the audit, scoring just 2. The Conservatives do even worse, with the lowest possible score of 1. There is very little attention given to the environment in the Conservative manifesto. Labour do put more emphasis on the environment, but get a low score as they lack any tough short-term commitments to tackle climate change. The Lib Dems provide far more detail than the other parties, and make stronger and more short-term commitments to tackling environmental issues.

The Conservatives score 2 for Fiscal Policy, the Lib Dems 3 and Labour 4. Labour’s plans to balance taxation and spending are the most transparent, and our author deemed them to be the best for the economy, jobs, and people’s lives. Labour propose to tax and spend around £50bn more a year, the Lib Dems propose to add a penny to basic-rate income tax to provide an additional £6bn for health and social care. The Conservatives will provide more of the same, and aim to eliminate the deficit on current spending by 2025 (the latest timeframe given of all the parties).

Labour and the Lib Dems both score 4, and the Conservatives score 2 for Health. All the parties pledge additional funding for the NHS, but the Conservatives promise significantly less at £8bn (in real terms) over the parliament, compared to £6bn each year promised by both Labour and the Lib Dems - although part of that £6bn would be allocated to social care by the Lib Dems whereas Labour pledge separate additional funding for social care. In all cases, the funds pledged are lower than required, according to the Nuffield Trust.

None of the parties inspire above “medium” confidence with their housing policies. Labour scores 3, the Lib Dems 2, and the Conservatives just 1. The current housing system is described as “dysfunctional” by the Conservatives, and “in crisis” by Labour, but none of the parties’ policies inspire confidence that this will have changed by the end of the next parliament. Unusually, all three parties want to make private renting offer more to its tenants, which should help people on lower incomes. Both Labour and the Lib Dems promise to end the "bedroom tax".

There is a clear difference between the Conservatives, who score just 1 on Immigration, and Labour and the Lib Dems, who score 4 and 3 respectively. The policy commitments of Labour and the Lib Dems offer the best chance of improving the lives of migrants in Britain. Conservative policies are highly likely to exacerbate migration-related poverty and place migrants at greater risk of social exclusion. Labour rejects the use of immigration caps, promising fair rather than strict immigration rules. In contrast the Conservatives include an explicit objective to reduce net immigration to tens of thousands.

Labour scores highest with a 4 for International Development, the Lib Dems are close behind with 3, and the Conservatives score just 1. All three parties promise to spend 0.7% of GDP on aid, with Labour making additional promises to bring in new rules to ensure that aid is used where it is most needed. The Conservatives repeatedly call for global free trade, in contrast to Labour who promise to support labour rights abroad and make sure trade agreements protect workers’ rights. Labour and the Lib Dems are both clear that Britain should welcome its fair share of refugees, the Lib Dems include the most detailed plans to implement this.

The Conservatives score 2, the Lib Dems 3, and Labour 4 for Social Security. None of the three parties fully tackle the two key challenges facing social security - the continued insecurity of employment and the spread of in-work poverty. Labour are proposing a wider reform of social security provision than has been seen since the mid-1990s - proposing to change the sanctions regime, change assessment regimes and generally challenge the demonisation of claimants. The Lib Dems share these concerns, but they don’t go as far as Labour, and retain a focus on an ethos of return to work.

For an election that many observers claim is about Brexit, there is precious little detail about Brexit in any of the three main parties’ manifestos (Barnard et al 2017). This absence leaves voters with very little to guide their judgements as to how any of the parties would negotiate with the EU, prepare the ground for Britain’s departure from the EU, or seek to prepare the British economy and British public services to ensure that the process of Brexit occurs without creating damaging economic inequalities or further deepening the poverty that is already witnessed in many areas of the UK.

Certainly, manifestos do not generally contain much in the way of detail. But most economists predict that Brexit will, in the short term at least, damage the British economy. Swati Dhingra, of the London School of Economics, estimates the impact from loss of trade will be in the order of an annual 3.0% reduction in gross domestic product (GDP).

There will be specific challenges to confront. Leaving the EU will require a new agricultural policy. The Conservatives speak merely of devising a new agri-environmental system. On the NHS, only the Liberal Democrats and Labour guarantee the position of EU citizens in the UK working in healthand social care. None of the manifestos clarifies how pharmaceutical regulation will be handled after the departure of the European Medicines Agency.

This being the case, we would expect the manifestos to lay out a plan capable of addressing each of these challenges, in order that stated commitments to economic inequality and poverty reduction can be made effective. In this short essay, we should like to bring four particularly notable absences to view.

First, immigration. There is little doubt either that immigration played a major part in shaping the outcome of the referendum or that it continues to matter to a large number of voters. Reducing immigration from the EU is likely to be an extremely complex undertaking, especially if it is to be achieved without potentially severe consequences for the British economy or for the provision of basic public services, and thus potentially severe consequences for poverty and economic inequality. Yet the parties choose to reveal remarkably little about their strategies. Labour and the Conservatives note that freedom of movement as established by EU membership will end with Britain’s departure from the Union, but neither sketch even the vaguest proposal for what will follow. The Conservatives do specify a target – reducing net migration to the tens of thousands – but identify neither a process for achieving it nor for calculating the cost either to specific sectors of the British economy or to the economy overall. The Lib Dems promise to maintain freedom of movement within the single market.

Second, trade. There has been much debate among economists and anti-poverty campaigners on the economic consequences of free trade deals and the difficulty in striking them. For some, the Brexit vote itself indicates a repudiation of the kind of open trade associated with EU membership, and with the broader globalism of the last few decades. For others, Britain’s likely withdrawal from the single market, and the trade possibilities that it guarantees, presage a potential severe dislocation for the British economy, likely to cause difficulties at least in the medium term for British workers and consumers in general, and especially for those struggling in the hardest parts of the labour market. Others still see Brexit as an opportunity to reorient trade away from the stalling EU economy towards emerging powers. Again, the manifestos are strikingly largely silent on this question. Each makes a commitment to seeking to maintain benefits akin to single market membership, while making little effort to explain either how such benefits are to be secured through negotiation or how such benefits could be maintained while the UK opens up to potentially contradictory rival trade deals with other major economic powers.

Third, the rebalancing of the British economy. The overreliance of the UK economy on a prosperous financial services sector, and the failure to generate high quality employment opportunities in other sectors and other parts of the country, has contributed to both poverty and economic inequality in recent years, and likely played a part in leading to the leave vote in the referendum. Once more, however, the manifestos are strikingly silent on the opportunities Brexit might present to address this long-standing difficulty. Labour does accuse the Conservatives of wishing to utilise the great repeal bill to deregulate the financial services sector still further, and to undermine employment rights, but there is scant evidence for that desire in the Conservative manifesto itself. Labour also outlines the possibilities of using a national investment bank to support local industries across the regions in the UK, in ways that might have previously been proscribed by EU state aids rules, but all manifestos privilege vague aspiration over concrete plans.

Finally, Brexit represents an enormous challenge to the British state. The need to draft the great repeal bill, along with the necessary accompanying primary legislation, while putting into place new national policy frameworks in areas like agriculture and fisheries, will provide the civil service with arguably its largest ever peacetime challenge. None of the parties adequately outlines how it will implement its policy priorities whilst this Brexit process is underway.

Barnard, C., Dhingra, S., Hunt, J., Macdonald, C., McHale, J., Menon, A., Portes, J. and Usherwood, S. (2016) Red, Yellow and Blue Brexit: The Manifestos Uncovered. The UK in a changing Europe. Available at http://ukandeu.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Red-Yellow-and-Blue-Brexit-The-Manifestos-Uncovered.pdf

The Conservative manifesto is very short on detail in this area. It states that we can expect a continuation of its current record. The Conservatives celebrate public service and will fund schemes “to get graduates from Britain’s leading universities to serve in schools, police forces, prisons, and social care and mental health organisations.” However, it is not clear how this will create change. What we need is a diverse workforce with an understanding of how real people lead their lives, often in poverty. It is unlikely that this going to be achieved by using highflying graduates as an elite taskforce. Labour and the Liberal Democrats both argue for the public-sector cap on wages to be relaxed, which is more likely to enable the recruitment of staff who will stay in post.

All three manifestos commit to tackling hate crime, domestic violence, and prioritising the victims of crime in general. The Conservatives and Lib Dems both advocate a punitive approach to offenders. However, punishment will not stop offenders from reoffending and there is a long history of more restrictive community sentences replacing less punitive community sentences rather than custody.

Both Labour and the Lib Dems include detailed, although slightly different, proposals relating to young offenders. Both parties emphasise restorative justice - a constructive approach if it is properly resourced and targeted. This is missing from the Conservative manifesto. The Lib Dems’ proposal to make the Youth Justice Board responsible for those under 21 fits with our increasing understanding of brain maturation.

The Human Rights Act is an important piece of safeguarding legislation and its repeal worries many legal experts and others, with its implications of the erosion of individual rights and freedom. Labour and the Lib Dems both commit to retaining the Act, whilst the Conservatives pledge to "consider our human rights legal framework when the process of leaving the EU concludes".

The aftermath of the Transforming Rehabilitation (TR) “revolution”, implemented by the coalition of the Conservatives and Lib Dems, has been very contentious. Many observers would agree that the private “Community Rehabilitation Companies” (CRCs) did not end up with the finances that they were expecting, and reviews of the work of the CRCs by HM Inspector of Probation have been very critical. TR has now been stopped and unsurprisingly it is ignored in the manifestos of these parties. Labour will “review the role of” CRCs, but does not argue for more to be invested into community supervision.

The Conservatives state that “prisons must become places of safety, discipline and hard work, where people are helped to turn their lives around”. The Lib Dems also pledge that prisons will have the remit to rehabilitate prisoners. However, it is hard not to be cynical about this on the evidence of what is happening currently. Politicians need to have the courage to state that a punitive mentality is unlikely to achieve this. The evidence we have shows that treating offenders holistically with respect, and offering the opportunity to receive education, support, and guidance is more likely to be successful.

The Centre for Crime and Justice Studies has also analysed the three manifestos and concludes that the Criminal Justice System is dominated by the police share of spending and staff (Garside, 2017). They are dubious about the benefits of increasing the investment into the police, advocated by all parties, especially Labour and the Lib Dems. Evidence shows that more front line policing does not lead to more convictions, although it may reassure the public to see more police presence. As so much police time is spent on non-crime matters it would make more sense to increase the number of mental health and social workers available to do this work. Using the police for this work stigmatises the most vulnerable and doesn’t use resources to maximum effect.

What is happening in terms of sentencing is worrying. The number of offenders given fines has increased massively, a punishment often on levied the poor. The number of offenders given community supervision has risen slightly, but is dwarfed by those fined. Those sentenced to custody remains high, with sentence length increasing.

With the rhetoric of “tough supervision” from the Conservatives and Lib Dems, and silence on this issue from Labour, we can expect to continue to see a high level of technical violations of community supervision for offenders who fail to keep to their conditions, especially for women. What’s needed is a new maxim: tough on politicians bidding up a macho approach to working with offenders.

This is not to say that supervising offenders is a soft option, it is not, but with political parties arguing for tough penalties it removes the voice of the offender and renders them passive, for penalties to be enacted against them, without the promise of working with them to encourage them to change and become active citizens.

Overall, Labour scores highest of the three parties and, in general terms, demonstrates a commitment to the poor and disadvantaged. In terms of criminal justice, it is disappointing that a fear of appearing soft on crime has resulted in a manifesto that lacks the outright punch of declaring support for offenders as well as punishment. This is typified by a repeat of the old New Labour mantra. For both the Conservatives and the Lib Dems there is the embarrassment of having to own the ill-considered and overly hastily implemented Transforming Rehabilitation “reforms” that introduced competition and a split in how offenders are supervised. Offenders are citizens and, without condoning their offending, we should be offering community support and supervision, not predominantly fines and custody.

Garside, R. (2017) Assessing the 2017 General Election Manifestos. Centre for Crime and Justice Studies. Available at https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/sites/crimeandjustice.org.uk/files/UKJPR%20Focus%2C%20Assessing%20the%20Manifestos%2C%20May%202017.pdf

In 2016, the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities found “grave or systematic violations” of disabled people’s rights in Britain.

For disabled people to lead good lives, society must act in all aspects of their lives - to remove barriers, to render buildings, transport and information accessible, and to provide jobs, social security, education, healthcare and social care. A human rights framework grounded in the “social model” of disability offers the best path forward - identifying lack of social action, not people’s conditions or impairments, as the problem.

The Conservatives focus on mental health, including mental health first aid training for staff.

Labour would deliver a special education and disability (SEND) strategy based on “inclusivity”, embed it in staff training, and extend school counselling.

The Lib Dems also focus on mental health: they would incorporate it in the personal, social, health and economic education (PHSE) curriculum and give teaching staff mental health training. All schools would provide immediate access to support and counselling, and the party would check new policies to see how they affect special educational needs and if they comply with the Equality Act 2010.

The Conservatives promise to get a million disabled people into work in the next decade. But beyond a national insurance holiday for their employers, and vague promises on workplace attitudes to mental health, they fail to show how.

Labour offer few specifics on disabled people: they seem to assume changes that help workers in general - like a “real living wage” - will help disabled people too. But the party does promise to enhance the Equality Act 2010 so that people can challenge workplace discrimination; to commission a report on expanding Access to Work; and to set a target on disabled apprentices.

The Lib Dems offer very little on employment. They pledge to publicise and expand Access to Work, while improving links between Jobcentre Plus, work scheme providers and the NHS.

The Conservatives will “push forward” with a plan to tackle hate crime (including disability hate crime). Labour will introduce annual reporting and an action plan to tackle it. The Lib Dems say nothing specific about disability here.

Labour follow the social model of disability. The party would bolster the Human Rights Commission’s powers and incorporate the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) into law. They would improve awareness of neurodiversity and make Britain “autistic-friendly”, make terminal illness a protected characteristic under the Equality Act 2010 and British Sign Language (BSL) a fully-recognised language.

Labour and the Lib Dems would keep the Human Rights Act. The Lib Dems say much about human rights, but nothing specific about those of disabled people.

All three manifestos promise to spend more on health and social care - the Conservatives £8bn (in real terms) on the NHS over five years; Labour £6bn a year on the NHS, plus £2.1bn a year on social care; the Lib Dems £6bn a year on both combined.

The Conservatives pledge a new Mental Health Bill placing “parity of esteem” (giving physical and mental conditions equal weight) at the “heart of treatment”; and to reform of the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service so that children are seen in an “appropriate timeframe” and in their own area.

Labour will give mental health the same priority as physical health, and start constructing a National Care Service. Labour and the Lib Dems would ring-fence mental health budgets and focus on needs of children and young people. The Lib Dems would “transform mental health support for pregnant women, new mothers and those who have experienced miscarriage or stillbirth”, and look to introduce a health and social care convention.

The Conservatives plan no big changes.

Labour promise to scrap “punitive sanctions”. They promise to abolish Personal Independence Payment (PIP) tests and (contradictorily) to treat mental and physical health equally within them. And they would replace ESA and PIP tests with a “personalised, holistic assessment”. No-one with a severe, long-term condition would be re-tested.

Both Labour and the Lib Dems would abolish the bedroom tax, bring back the work-related activity part of Employment and Support Allowance (ESA), and scrap the Work Capability Assessment (WCA). Both would change Carer’s Allowance - Labour to make it more generous, the Lib Dems easier to claim.

The Lib Dems would raise working-age benefits in line with inflation, and replace the WCA with a local authority-run “real world” test based on local labour markets.

The Conservatives say they will “review” access to transport and change regulations where appropriate.

Labour would introduce legal duties to improve accessibility. They pledge to improve access for disabled sports fans.

The Lib Dems will continue the Access for All programme, and prioritise improved access to transport; improve blue badge scheme rules; make more stations wheelchair accessible; benchmark accessible cities; and extend the Equality Act 2010 to cover private hire vehicles and taxis.

The Lib Dems alone launched their manifesto in a range of accessible formats, showing commitment to disabled people’s participation. Labour followed suit, but the Conservatives have not.

Labour follow the social model of disability, but mention “people with disabilities”, not “disabled people”, throughout. (The British disabled people’s movement use “disabled people” to emphasise discrimination experienced, not impairments or conditions themselves, as the core problem.)

The Lib Dem and Labour manifestos are most likely to relieve disabled people’s poverty and other barriers to their flourishing.

Labour offer the most comprehensive response to disabled people’s needs and demonstrate the greatest commitment to their rights - followed by the Lib Dems, then the Conservatives.

A good education system in the UK would establish the foundations for all children to flourish throughout their lives. Education is vital in establishing a just society, when it minimises educational and social inequalities. Compulsory education should ensure that children are well fed and cared for, developing their critical and analytical capacities, starting a lifelong love of learning that responds to their intellectual curiosities and learning practical life skills. It should teach them about their world and society and how to relate to it. The curriculum needs to respond to modern conditions and address social diversity. An education for flourishing would encourage a sense of individual identity, of belonging to a community and the exercise of freedom. Higher, further, and adult education also offer these opportunities, as well as enhancing economic opportunities.

Quality education is about more than exam scores: it’s about the people it works for. Systemic change is needed to redress the emphasis currently placed on exam scores, identifying alternative means of evaluating quality teaching.

Educational institutions need: well-qualified, passionate, and secure staff; adequate infrastructure; sufficient time and leisure; a consistent curriculum; and a consistent, sustainable funding structure. Constant reforms strain the system and individuals. The explosion of different types of schools has made the system more difficult to navigate for families with lower levels of education and economic security. Poorer children end up in worse schools, so that local school hierarchies compound educational and social disadvantages. Selective admission criteria would make this worse. The emphasis on exam-based performance criteria encourages educational competition, which undermines its creative democratic potential to contribute to a flourishing society.

The Conservatives and Labour have clear headlines: the Conservatives want a “Great Meritocracy”, which they are going to achieve by giving everyone access to a world class education. Labour wants to create a National Education Service, cradle to grave, like the NHS. The Liberal Democrat headline is to 'put children first'.

Both Labour and the Lib Dems would stop free schools, academies, and grammar schools. The Conservatives are sticking to their policies on these, and would remove the ban on selective admissions. From an equity perspective, selective admissions or grammar schools have been found to disadvantage those not selected, and children from poorer families are significantly less likely to get in (Sibieta, 2016). This has a domino effect on getting into university, and on social mobility in later life.

Ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation, and regional variation are not high priorities in education in any of the three manifestos. However, the Lib Dems do commit to including gender and LGBT+ in the curriculum and through teacher training. Both they and Labour also make specific commitments with regards to mental health and to increasing BAME participation in apprenticeships.

All three manifestos address the teacher recruitment crisis and suggest they will reduce bureaucracy. Both the Lib Dems and Labour propose enhancing bursaries, improving conditions, and removing the public sector pay cap. Labour also specifically commits to reducing class sizes.

Both the Labour and the Lib Dem manifestos have explicit commitments to adult education, through further education and lifelong learning. They both promise to restore the Education Maintenance Allowance. Labour commits specifically to restoring English language classes that are free at point of use, which perform an important function for social integration particularly for refugees and asylum seekers. The Conservatives have a major plan to create institutes of technology “in every major city in England” which will offer STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) and vocational training. They also promise unspecified ‘investment’ in further education colleges. All three parties commit to increasing the quality of apprenticeships. Labour’s big campaign promise to remove university tuition fees appears in the manifesto, fully costed. The removal of tuition fees is a fiscally realistic proposition which, in combination with appropriate widening participation policies, would contribute to reducing the inequalities of higher education. The Lib Dem manifesto ignores a number of equity issues that have arisen since the raising of the tuition fee cap to £9,000, such as the decline in part-time student numbers. The Conservative manifesto mentions very little about higher education, presumably because the Higher Education Bill has been signed into law covering most of their agenda.

Labour’s is the only manifesto to cost all specific promises. The Lib Dems provide an overall figure for the total cost of their commitments, but not specifics. The Conservatives don’t cost their education plans at all, and in particular the establishment of institutes of technology is likely to be an expensive endeavour. None of the manifestos make their evidence base clear for why they adopt particular proposals.

Scott, P. (2017) Jeremy Corbyn’s plan to end student tuition fees is far from barmy. The Guardian (online). https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/may/02/jeremy-corbyn-end-student-tuition-fees Sibieta, L. (2016) Grammar Lessons. Society Now. Autumn 2016, Issue 26. 18-19.

All of the manifestos pay considerable attention to employment, situating it within broader agendas related to social justice, fairness and equality. “Prosperity for all” is a key feature and many of the policies are clear appeals to win back the JAMs, the ‘ordinary working people’ whose disillusionment with political processes was brought into sharp focus by the Brexit vote.

Policies focus on wages at the lower end of the labour market and on job security - at a time where the gig economy and zero hour contracts affect growing numbers of workers. In all cases they show a move away from the current neo-liberal orthodoxies, being much more interventionist in areas such as job creation and protection and workers’ rights.

When assessing the three parties’ policies against the five ideal social outcomes, no shortage of policies are proposed. However, the means by which these policies would be operationalised and come together as a mutually reinforcing set of policies with transformative potential is much less well-articulated. This is particularly the case with the policies specifically aimed at “ordinary people” -- where rhetoric and populist soundbites seem to take precedence over fully-realised proposals with specific mechanisms for implementation.

All parties present proposals to increase the net wages of the lowest earners and the concept of a “living wage” is used in all three manifestos.

The Conservatives would increase the National Minimum Wage (NMW), referred to as the “National Living Wage”, to 60% of median earnings, but it is not clear why this figure (estimated at around £8.75 per hour by 2020) would represent a “living wage”.

Labour would increase the NMW to the level of an accepted “Living Wage” (around £10 per hour by 2020) and extend it to all over 18s not on apprenticeship wages; but the party fails to clearly explain how employers would fund such an increase in their wage bill. In fact shedding of lower-paid jobs and stagnation in the pay of lower-middle earners are possible outcomes.

The Liberal Democrats propose to consult on setting a genuine living wage.

Work that is “good” is also a key theme in all the manifestos. However, while the Conservative manifesto primarily describes “good work” in terms of pay levels and job security, the Labour and Lib Dem manifestos extend the concept to encompass job quality and fulfilling work - although proposals in these areas tend to read more as aspirations than concrete, achievable policies with measurable outcomes.

Policies related to workers’ rights are common across the three manifestos, but this is also an issue on which we see the most political grandstanding.

How measures such as “properly protecting” the rights of workers in the gig economy (Conservatives) or “modernising employment rights” (Lib Dems) might be achieved in practice is left unclear, and the costs of proposals such as the right to request leave for training (Conservatives) or reforming in-work benefits (Lib Dems) are not given.

Consequently, all three manifestos promise “rights” that are substantive in themselves, but are not backed up by clear procedures for enforcement of these rights.

Worker representation and participation in decision-making is addressed only briefly and is largely related to employee representation on boards of public listed companies. The Lib Dems propose a two-tier German-style system of representation. The Conservatives present three options: nominating a director from the workforce, creating a formal advisory council or assigning specific responsibility for employee representation to a designated non-executive director; but this latter option raises questions of the extent to which such a director would be viewed as legitimate by the workers they purport to represent. Labour also proposes to strengthen the role of trade unions.

The stated aim of all three parties to introduce policies that “work for everyone” provides a clear impetus for addressing issues related to equality in the workplace. The Conservatives have made the “burning injustice” of inequality a key rallying-cry in their manifesto, while Labour’s “For the many and not the few” takes a similarly strident tone.

However, when it comes to turning these claims into policies for the workplace, the message is much less strong. Employers will be “asked” and “encouraged” to publish data on, for example, the gender pay gap, and unspecified measures will be taken to promote positive practices. Flexible working policies largely focus on making waged work viable for groups that might otherwise be excluded, rather than on promoting work-life balance as a means of achieving more fulfilling life. The Lib Dem manifesto has the largest number of specific, concrete policies, but their cumulative impact would not be great, precisely because they are very specific and limited. There is little recognition in any of the manifestos of non-waged work, beyond helping those with caring responsibilities access waged work.

The Conservative manifesto has the most coherent set of policies linking supply and demand and regional economic development; these are articulated through its Modern Industrial Strategy. Industries of strategic value would be supported, while young people, in particular, would be helped by training and skills development policies. In contrast to the party’s approach to benefits policy, supply-side employment policies focus more on reward; so, for example, choosing to engage in training to develop skills would be rewarded by access to the most desirable - i.e. highest paid - jobs.

The Lib Dems also have a strong focus on job creation in the regions and name specific industries and projects they would facilitate as part of their industrial strategy, as well as the levers they would use to encourage progress.

But in both cases, it is unclear what impact the policies outlined would have on the lower-waged, lower-skilled workers who are most at risk of poverty. Key industries are largely those requiring higher skill levels and those who will benefit most are those who already have higher skills or who have the capacity and capability to acquire them.

Labour outlines an industrial strategy that identifies key strategic industries and links the strategy to the creation of a National Education Service for England. However, the Labour manifesto provides less detail about the nature of these jobs, and how its industrial strategy would address the party’s own concern that some parts of the country are being left behind.

Overall, when we consider whether the employment policies outlined in the manifestos promote flourishing lives and reduce poverty, the key weakness is not that the manifestos lack policies in these areas, but that all three parties appear to be sacrificing quality for quantity.

The Conservatives explicitly see employment as a route out of poverty, but when the rhetorical soundbites are set aside, the concrete strategy for taking people out of poverty is largely reliant on achieving higher wages through mechanisms such as the development of higher level skills. This fails to take account of the fact that this will not be achievable for all lower-paid workers and that poverty is a multi-dimensional concept of which income levels are only one part.

The Labour manifesto is aspirational, but there are questions about how achievable their policies would be - particularly as many of their costings rely on there being no pushback from employers and others who are expected to bear the weight of paying for Labour’s proposed reforms.

The Lib Dems present the most realistic and achievable set of policies, but in doing this they have, to a certain extent, sacrificed ambition. Their policies are small scale, with bigger changes that would affect the lives of the poorest being left to future consultations.

In all three manifestos, there are laundry lists of aspirations, “we will do this”, “we will stamp out that”, but information on why such things might be desirable or how they might be achieved is severely lacking.

If all the policies were introduced, would they promote flourishing lives? Perhaps.

Could all the policies be introduced? Probably not.

Cost implications and monitoring are rarely considered in any of the manifestos and some policies lack appropriate levers to ensure the kinds of positive outcomes that the capability approach, and indeed the parties’ own stated values, demand.

The relevant policy areas that feature most in the three manifestos are energy, transport, housing, farming, access to green spaces, air quality, and climate change.

The Conservative manifesto gives very little attention to the environment or to sustainability. There is a commitment to meet the 2050 carbon target, but this is a distant target and there is nothing to suggest that the environment will be a priority over the next five years. Most reference to the environment is contained in a discussion of energy policy, which is first and foremost aimed at delivering low cost energy. Surprisingly, no mention at all is made of nuclear energy, whilst wind energy gets one sentence. In contrast there is a whole section on shale oil which suggests fracking will be a cornerstone of plans for low cost energy. The arguments seem confused.

Firstly, it is claimed that growing shale gas exploitation can help reduce carbon emissions, whereas most commentators would agree that locking into new fossil fuel infrastructure will make it harder, not easier, to meet carbon targets. Thus, there is little confidence that manifesto proposals will ensure that the planet remains a safe place for human flourishing in the longer term.

Secondly, shale exploitation is presented as giving choice to local communities, suggesting some democratisation of environmental governance, but this sits uncomfortably with the statement that “major shale planning decisions will be made the responsibility of the National Planning Regime”.

Whilst Labour and the Liberal Democrats devote more manifesto space to concerns about air quality, the Conservatives say little beyond another distant target, that all cars and vans will be zero emission by 2050. Such targets are simply too far off to give any confidence that much will be done within a term of office. There is a welcome pledge that this generation will leave the environment in a better state for the next generation. However, again, targets are quite far off. In effect, the generation in question starts now, meaning that the pledge will be approached via a ‘25 Year Environmental Plan’, and with no interim targets specified.

The Labour manifesto places rather more emphasis on the environment and scores slightly higher than the Conservatives for containing some more specific commitments that would be progressive in their effects. Nevertheless, the manifesto still lacks any tough short-term commitments and remains largely vague on flagship targets related to climate change.

Efforts to improve energy efficiency include commitments to insulate four million homes and tighten efficiency standards for landlords. Efforts to reduce air pollution include a promise to retrofit “thousands” of diesel buses in areas with severe air pollution, and a new Clean Air Act. Given that poorer people are more likely to live in areas with poor air quality, these are progressive policies that can help ensure health and safety requirements for human well-being. However, these policies still lack any detailed, time-bound commitment.

Unlike the Conservatives, Labour promise to ban fracking, on the basis that it would lock the UK into fossil fuels beyond 2030, a commitment that is considered positively by this audit. They also support new nuclear power provision, which is considered neutrally here - whilst nuclear power reduces dependence on fossil fuels, there are considerable environmental costs such as uranium mining, provision causes anxiety for local communities, and nuclear power has to date required large financial subsidies that could otherwise go into renewable energy. On the basis of carbon policies, Labour are judged to provide stronger assurance than the Conservatives in terms of safeguarding planetary conditions for human flourishing, but this policy area is still rather weak.

The Lib Dems’ manifesto is very clearly a step above the Conservative and Labour manifestos in relation to environmental policymaking. It is superior in the scope of the issues it embraces, the strength and timeline of its commitments, and in the attention to detail. There is considerable overlap with the Labour manifesto, but the Lib Dems go further: four million homes will be insulated, but with the more precise commitment to do this by 2022, and to prioritise the fuel poor; diesel engines will be addressed, but including a scrappage scheme, a ban for cars by 2025, and all taxis and buses to be ultra-low or zero emission within five years.

In energy policy, fracking is opposed and there is a tough target of 60% renewables by 2030. Nuclear energy is accepted as part of the mix, but only with conditions around dealing with the waste issue and ending subsidies.

Energy and transport policies are the cornerstone of a policy to bring in more stringent carbon deadlines: 80% reductions by 2040 and zero net carbon emissions by 2050. Such thinking is extended to commitments to reduce waste and reduce the UK’s net consumption of a range of environmental resources. Such policies contribute to wellbeing in material ways, for example through the health benefits of cleaner air. But they may also make more subtle contributions to wellbeing because they provide citizens with the opportunity to consume more ethically. Given a choice, we prefer energy, transport, food etc. that is not produced at the expense of harm to others.

All three manifestos mention protecting the countryside and green spaces, and all make special mention of supporting a ‘blue belt’ of marine protected areas. But the Lib Dems again go further. They pledge to: maintain EU environmental standards post-Brexit; bring in legally binding natural capital targets; create up to a million acres of new green spaces; plant one tree per person over the next 10 years; and rebalance agricultural subsidies towards the environment and other public goods - including a progressive element to support small farmers.

Overall, it is clear that this election is not going to be fought over environmental issues and the Conservative and Labour manifestos are disappointing in the level of commitment and thought that has gone into this policy sector. The Lib Dems’ manifesto contains much stronger and more coherent policy in this area.

All three parties announce some balanced-budget target (the Conservatives by 2025, Labour by 2022, the Liberal Democrats by 2020). None ask if this goal is desirable or feasible.

Britain needs public investment, funds are available and borrowing costs low. And governments cannot control public deficits: they depend on the scale and nature of economic activity. So any government seems certain to miss its targets - yet none of the parties say how they would respond when that happened.

Public net investment now runs at 2% or more of GDP. So which budget a party plans to balance - capital, current or both - changes markedly the scale of public-sector activity, in turn affecting GDP and employment.

The Conservatives still want to balance the budget, but by 2025. The Lib Dems now promise to eliminate the deficit on current spending by 2020. Labour plan to balance the current budget by 2022.

Conservatives

The “deficit is now back to where it was” before the 2007-8 crash, but “there is still work to do”. So “the fiscal rules announced by the chancellor … will guide us to a balanced budget by the middle of the next decade”. A significant current budget surplus would accompany some borrowing for capital investment.

Labour

Eliminate the deficit on current spending in five years and borrow to fund capital investment. Tax and spend more (around 2.5% of GDP), and invest more (around 1%).

Liberal Democrats

Reject planned surpluses on the combined current and capital budget. Eliminate the deficit on current spending by 2020 (not, as now forecast, 2018-9). Then increase current spending in line with economic growth. £100bn more infrastructure investment (1% of GDP per year, if spread over five years).

Labour propose to tax and spend around £50bn more a year (around 2.75% of GDP). They allot £25.3bn for education, £7.7bn for health and social care and £4.6bn for pensions and welfare. They promise a ten-year, £250bn infrastructure investment fund covering transport, energy, communications, scientific research and housing.

The Lib Dems say they would add a penny to basic-rate income tax, raising £6bn to spend on health and social care. They promise £100bn more infrastructure investment, focused on housing, schools, hospitals, hyper-fast fibre-optic broadband, renewable energy, roads and rail.

Labour and the Lib Dems would stop capping public-sector pay rises at 1%. The Lib Dems would increase wages with inflation. Labour say “public sector workers deserve a pay rise after years of falling wages”. They estimate this would cost £4bn.

Labour’s fiscal plans are healthiest for the economy and employment, the Lib Dems’ less so, the Conservatives’ least.

Labour’s detailed plans are the most transparent, the Conservatives’ the vaguest.

No problems arise around sustaining public deficits, which are falling. But no party mentions Britain’s true economic sustainability problems: big current account and trade deficits plus rising household debt.

Due to the media and public concerns of poor hospital performance, missed targets, growing privatisation and large NHS deficits, health continues to be a major focus for the three main political parties in 2017. A good level of health is essential for people to flourish, to achieve this enough resources and opportunities are needed for citizens to access healthy housing, food, environment and a well-functioning NHS. To achieve a flourishing society government must co-ordinate various policy areas such as education, housing, employment, and the environment. In terms of health policy, government must take a broad view that includes health promotion, illness prevention, and public health services. Sufficient financial resources are needed so that the health and social care system can guarantee individuals a comprehensive range of high quality services within a reasonable time frame. Thanks to social and medical progress we are an increasingly aged population that requires growing support from social and health care services. At present these services are too limited and of variable performance, spending needs to be substantially increased to sustain a good quality health and social care system to improve and maintain the population’s holistic health needs.

Mental health is a focus for all three manifestos; committing to give mental health services parity with physical health. The Conservatives will encourage the public to enrol on a new basic mental health awareness training programme and recruit 10,000 more mental health professionals, but no supporting funding details are provided. While the Conservative manifesto focuses on the NHS, the Liberal Democrats and Labour manifestos explicitly discuss the importance of wider services such as public health, illness prevention and health promotion. In addition, the Lib Dems explicitly state the importance of the wider determinants of health such as housing and clean air, committing to “publish a National Wellbeing Strategy, which will put better health and wellbeing for all at the heart of government policy”, proposing the most holistic vision of health of all three parties. Labour commit to tackling the link between child ill health and poverty and will set aside £250m for a Children’s Health Fund.

In non-clinical policy issues, Labour will scrap the current pay cap for NHS workers, reverse any privatisation activities in the NHS and abolish the 2012 Health and Social Care reforms. The Lib Dems will also scrap the NHS workers’ pay freeze. The Conservatives are committed to the on-going NHS reforms, they will introduce a new GP contract that will provide seven day GP services by 2019, again there are a lack of details on how this will be done.

In response to the identified challenges of a growing elderly population and an increasingly cash strapped NHS, all three parties respond by committing to differing levels of NHS spending over the parliament. The Conservatives will provide £8bn (in real terms), the Lib Dems £30bn (for both the NHS and social care) and Labour £30bn for the NHS alone, but a leading health thinktank (Nuffield Trust) states that these are all less than is needed. As a highly equitable and progressive service, it is essential that the NHS is properly funded and does not become a public service that only serves the poor. All three manifestos recognise the challenges of funding social care services and state that health and social care services need to be integrated. The Conservatives will “encourage” this, while the Lib Dems and Labour explicitly want to integrate services and budgets. Labour dedicate a section of their manifesto to social care, proposing a National Care Service, and will commit £8bn to social care and increase the payments for carers.

On the funding side, both the Lib Dems and Labour clearly commit to raising the extra spending for health and social care from increased taxations, the Lib Dems will raise income tax by 1%, while Labour will increase taxes for people earning over £70,000 and large corporations. The Conservatives on the other hand do not explain where the extra NHS expenditure will come from, but do give some guidance in terms of social care. Under their plans everyone with assets over £100,000 (such as owning a house) will have to pay for all their social care needs. However, there was some confusion over this policy a few days after the manifesto was published and it is now unclear what their policy in this area will be, but there will be an upper limit to an individual’s financial liability.

As the incumbents, the Conservative’s health proposals are about more of the same. The Lib Dem and Labour manifestos offer more detailed plans on how health and social services could integrate, and propose new initiatives such as Labour’s Children’s Health Fund and National Care Service and the Lib Dems’ National Wellbeing Strategy. In terms of spending, Labour offers large increases, the Lib Dems offer moderately large increases, and the Conservatives commit only modest amounts. Only the Lib Dems and Labour suggest how their funding commitments will be paid for.

The aim of housing policy should be to provide decent quality homes, at affordable costs, with sufficient choice to meet the increasing diversity of household circumstances, sufficient security to enable life planning, and without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. Parts of the UK are currently experiencing severe housing shortages, which disproportionately affect the poorest in society.

All three manifestos identify serious problems with the housing system, describing it as: “dysfunctional” (the Conservatives) and in “crisis” (Labour). However, none of the parties presents a clear strategic view of the changing housing system. The Conservatives and Labour want to arrest the decline in home ownership – but how much? For whom? At what cost? All three parties want to extend the standard private rented tenancy to three years. But it is not clear whether this is enough to provide suitable tenure for families - given that school careers last seven years.

All the parties are concerned about affordability. However, none seem to be focusing on the affordability problems of the poorest - fuel poverty gets a mention, but none of the manifestos consider the 21% of people who are ‘housing poor’: poor once they have paid their housing costs. None of the three manifestos comments on the fact that the Department of Communities and Local Government capital budget is less than half what it was in 2010, or say if this “new normal” level is going to be enough to fix the problems.

All three parties promise a substantial increase in new housing development, with 200,000-250,000 new homes per year, compared to the 140,000 built in 2015-16 in England. This is a dramatic boost for the profile and ambition of housing policy. However, none of the pledges are fully credible without more details setting out how the new homes would be planned, delivered, and paid for.

The Liberal Democrats promise a “significant increase” in “social and affordable” housing. Labour says social housing development will reach 100,000 per year by 2022 (up from 28,000 in 2015-16). The Conservative manifesto gives no sense of what proportion of pledged new homes will be “affordable” (and recent Conservative policy has made “affordable housing” less affordable).

Investment in new homes might be expected to reduce house prices through sheer supply and demand. However, even if the planned increase in development is achieved, it would add no more than 6% to the total stock in England by 2022. Thus it cannot be expected to lead to more than a 6% drop in prices. That’s less than the market can vary in a single year for any number of reasons.

The Help to Buy scheme to improve access to home ownership for low and medium-income households is currently funded to 2020, although it isn’t mentioned in the Conservative manifesto. Help to Buy has been criticised for its cost, for increasing prices, and for not helping people most in need. However, Labour has promised to retain the scheme until 2027.

At this election, all the three main parties want to make private renting offer more to its tenants, a situation unheard of for decades, and one which should help people on lower incomes. Labour will make three year tenancies the norm, ban lettings fees for tenants, and provide “new consumer rights” for tenants. Landlords who want to be able to claim housing benefit will have to show that homes are fit for human habitation. The Lib Dems will also peg rent increases to inflation. However, the Conservatives promise only to encourage landlords to offer longer tenancies. None of the manifestos considers whether greater rights for tenants will mean more reluctance of people to rent homes out, or higher rents, or how the enforcement of higher standards will be paid for.

Both Labour and the Lib Dems promise to end the “bedroom tax”. They would also restore housing benefit to people aged 18-21. However, many other changes to housing benefit under austerity have affected other groups, and would be more costly to government - and beneficial to claimants - if repealed. To maintain existing affordable housing, Labour will end the Right to Buy scheme, following the 2016 precedent in Scotland, and the Lib Dems will allow councils the option to end it. Labour will reverse the Housing and Planning Act 2016, to restore “classic” social housing with indefinite rather than five-year tenancies.

Only the Conservatives mention social class. They state that worse school results for white working class boys are among the “burning injustices” of society, and that high house prices bar them from popular schools. While this manifesto may offer support to those working class people who are able to use the Right to Buy or Help to Buy, it does not help the JAMs who are “worrying about paying the mortgage”, working class people in social renting, or reluctant private tenants who wish they were in social housing.

The current system of housing subsidy and taxation is leading to increasing disparities in wealth. Labour plans to review council tax and to investigate a land value tax. The Lib Dems propose to charge double council tax on second homes and “buy to leave empty” homes. The printed Conservative manifesto contained a radical proposal for a poor-health based property tax, already dubbed the “dementia tax”, which would substantially affect homeowners who, through bad luck, need either domiciliary or residential care. However, on 22 May the party changed its policy, to create a new kind of double lock for older people: care users will pay the lesser of two amounts: 1) up to their last £100,000 in equity, 2) a set maximum (value as yet unknown).

All three parties promise to end street homelessness, by 2022 (Labour) or 2027 (the Conservatives). All three plan to implement a national strategy, and all propose “Housing First” services, which take people directly from the streets to independent accommodation. None explain how the necessary one bedroom flats will be found or funded.

The Homelessness Reduction Act 2017 (derived from a private member’s bill) broadened the range of people entitled to help from councils to prevent or relieve homelessness. However, there is a big question over whether local authorities have the resources to meet these new duties.

If the UK housing system is “dysfunctional” and in “crisis” on election day, none of these three manifestos suggest it will be working much better by the end of the next government, and poorer people will continue to take the brunt of problems.

The Liberal Democrats’ emphasis on equal opportunity, and a rejection of racism against migrants, are valuable starting points for immigration policy. The manifesto acknowledges migrants as a benefit to society in expanding people’s horizons and encouraging tolerance, rather than only as essential to the economy. The promise to offer sanctuary to 50,000 Syrian refugees by 2022 is an improvement on the current government’s pledge to resettle 20,000 by 2020. Although the Lib Dems promise to offer safe and legal routes to Britain for refugees to prevent dangerous journeys, they also promise strict control of borders. This will mean people will still be forced to travel irregularly, undertaking treacherous journeys. Positive elements in the manifesto include offering resettled unaccompanied minors indefinite leave to remain, thereby reducing the threat of deportation once they turn 18, and ending indefinite immigration detention by introducing a 28-day limit on detention. Despite the emphasis on equal opportunity, the manifesto differentiates between high-skilled, EU, student, and other migrants, guaranteeing the former opportunities for migration. The Lib Dems support the principle of free movement across the EU and will seek to retain this in any deal negotiated for Britain outside the EU. A priority will be the protection of rights of EU nationals in Britain.

Labour rejects the use of immigration caps and recognises the economic and social contributions of migrants. The manifesto promises fair rather than strict immigration rules. Perhaps the most valuable promise Labour makes is not to discriminate between people of different races, and to protect migrants already working in Britain regardless of their ethnicity. Also significant is Labour’s promise not to scapegoat migrants, for example by cutting public services and pretending this is the consequence of immigration. This will help counter populist, hostile, and prejudiced views about migrants that are based on misinformation.

A welcome development is the promise to remove income thresholds for migration to Britain. However, this will be replaced with a prohibition on recourse to public funds. This exclusion from welfare is likely to impact unemployed or low-paid migrants’ ability to flourish in Britain. Like the Lib Dems, Labour promises an end to indefinite immigration detention, a welcome move which will reduce the likelihood of vulnerable individuals being exposed to psychological and physical harm. A preferred outcome would have been an end to immigration detention altogether, which would remove the risk of detention-induced harm.

The manifesto promises to end the exploitation of migrant labour by cracking down on abusive employers, increasing work inspections and prosecuting employers not paying the minimum wage. This would be a positive move towards reducing the precariousness migrants face in Britain. Labour also promises to protect the rights of migrant domestic workers and take a ‘fair share’ of refugees, although the manifesto does not stipulate what this means in numerical terms. Labour promises to guarantee existing rights for EU nationals living in Britain, facilitating their acquisition of permanent residence and British citizenship.

The Conservatives offer the worst social outcomes for migrants. The manifesto proposes to reduce and control immigration. This promise is followed directly with a resolve to defend the country from terrorism and other security threats. The suggestion that migration and terrorism and security threats are somehow connected is dangerous and inflammatory. This use of language contributes to misplaced fears about migration as well as to the stigmatisation and targeting of various migrant and other racialised communities. The creation of a hostile environment for migrants puts them at risk of physical and psychological harm and enhances their likelihood of experiencing violence, precariousness and social exclusion.

The Conservatives are clear about prioritising highly skilled migrants over other migrants. The effect of this will be the continued facilitation of migration for those with access to resources, at the expense of migrants who do not meet this criterion. The manifesto clearly expresses the view that immigration into Britain is ‘too high’ and makes it an explicit objective to reduce it to tens of thousands. ‘Unskilled’ migrants are to be excluded along with migrants from outside the EU, international students, and those wishing to unite with their families. The manifesto promise to increase the earning threshold for those wishing to reunite with families will exacerbate existing problems of separated families, and the psychological and material difficulties migrants in this situation face. Present in the Conservative manifesto is an assumption that the presence of migrants is problematic for British society, that racialised communities contribute to a lack of cohesion, practice a particular religion, and live according to a particular culture, one that is not necessarily compatible with ‘British values’.

These assumptions are harmful in serving to ostracise migrant communities and construct them as inherently problematic for British society. The assumptions contained in the manifesto are both indicative of, and risk feeding, racial prejudice against migrants. The promise to recover the cost of medical treatment from people without UK residency, and to raise the surcharge for access to the health services for migrant workers and international students, risks impacting negatively on the health and well-being of migrants. Undocumented migrants and those in low-paid employment might be dissuaded from accessing healthcare due to prohibitive costs. Such policies will further undermine the health, safety and wellbeing of migrants, cutting them off from support services, and contributing to their marginalisation. The Conservative manifesto makes a lukewarm gesture towards refugees. Although it claims Britain is a place of sanctuary, it states that asylum applicants who make it to Britain will not have their protection prioritised. The manifesto promises that a Conservative government will work to reduce asylum claims made in Britain. Such a policy will exacerbate the number of deaths and injuries of people who are forced to undertake dangerous journeys in their attempt to seek safety in Britain. The Conservatives promise to secure the entitlements of EU nationals in Britain.

In summary, the policy commitments of Labour and the Lib Dems offer the best chance of improving the lives of migrants in Britain. Conservative policies are highly likely to exacerbate migration-related poverty and place migrants at greater risk of social exclusion, violence, abuse, and premature death. On balance, Labour promises greater substantive protection measures for vulnerable migrants, such as those at risk of exploitation in the workplace. The Labour manifesto also inspires greater confidence as regards feasibility in its provision of some indication as to how policies will be implemented in practice.

The Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats all promise to spend 0.7% of GDP on aid. But the Conservatives suggest they would change the rules on what counts as aid, implying they would pay out less. Labour alone promise to bolster the aid budget, regulate the share paid to private contractors and enforce “new rules to ensure aid is used to reduce poverty for the many, not to increase profits for the few.”

All three parties say they support the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), but to different extents. Labour promise annual reports to Parliament on SDG performance. The Lib Dems say they will audit new trade, investment and development deals to ensure compliance. But the Conservatives fail to show how they would implement or monitor this.

Labour and the Lib Dems acknowledge that tax havens and tax evasion harm developing countries. Labour promise new financial transparency rules in crown dependencies and overseas territories. The Lib Dems support country-by-country reporting rules to stop multinational companies shifting profits offshore, and pledge to tighten rules against tax havens. The Conservatives stay silent on the issue.

Labour alone propose to make redistribution and social justice development objectives, declaring fair trade and state sovereignty key principles. They promise to let developing countries access UK markets, support trade unions and labour rights abroad, and make sure trade agreements protect workers’ rights. They oppose investor-state dispute mechanisms and commit to safeguard the rights of states to protect public services and regulate in the public interest. And they promise to make British businesses that operate abroad – and the global supply chain for British goods – uphold human rights, workers’ rights, and environmental standards. The Conservatives, by contrast, call repeatedly for liberalised trade (“We will be the world’s foremost champion of free trade”) and demonstrate no concern for developing countries’ needs.

All three parties make commitments to end modern slavery.

No party calls for fairer voting power in the World Bank, IMF, or WTO - though the Conservatives promise to “reform multilateral institutions… to protect and help the world’s most vulnerable people”. On intellectual property Labour are silent, while the Lib Dems pledge to maintain the status quo and the Conservatives to tighten the rules.

All three parties promise to support the Paris Agreement, but the Lib Dems come out strongest on climate change. They propose a Zero-Carbon Britain Act, setting legally binding targets to cut greenhouse gas emissions 80% by 2040 and to zero by 2050. They also pledge to source 60% of electricity from renewables by 2030.

While Labour never pledge to cut emissions to zero, they promise a 60% renewable target for all energy (not just electricity) by 2030. The Conservatives pledge to cut emissions 80% (from 1990 levels) by 2050.

Labour and the Lib Dems say they would ban fracking. But the Conservatives leave fracking on the table and support a US-style shale gas programme.

Only the Lib Dems promise to spend more on international environmental co-operation, not only on climate change but also to help tackle illegal, unsustainable trades in timber, wildlife, ivory and fish.

The Lib Dems and the Conservatives say they support education in developing countries. The Conservatives emphasise women’s and girls’ education; Labour pledge to support women’s social movements.

While all three parties say Britain must help refugees, Labour and the Lib Dems are firmest that Britain should welcome their fair share, and the Lib Dems offer the most detailed plans.

The Conservatives mention efforts to curb microbial resistance and emerging tropical diseases. The Lib Dems stress vaccination, and especially tuberculosis, HIV, and malaria.

The Conservatives promise to help end the “subjugation and mutilation of women”, “sexual violence in conflict,” and violence based on faith, gender or sexuality. The Lib Dems promise to support family planning.

The Labour Party offer a clear structural analysis of global poverty and underdevelopment, taking a strong stand in support of a fairer global economy. Labour’s policies are the most likely to empower developing countries and their social movements to help citizens flourish. The Lib Dems convince less here, but match Labour in concern about tax evasion and illicit financial flows.

Climate change – perhaps the century’s key development issue – gets the strongest treatment from the Lib Dems, followed by Labour, and trailed by the Conservatives.

The Conservatives promise to back liberal interventions on gender and sexual violence, but say little on structural drivers of underdevelopment. Their veiled attack on the aid budget, silence on illicit money flows from developing countries, unqualified support for global free trade, and weakness on climate change, all call into question their commitment to meaningful international development.

No party promises to help improve governance, the rule of law, or media freedom in developing countries. None call for fairer voting power in the World Bank, IMF, and WTO. And none call for debt cancellation, fairer intellectual property rules, or curbs on land grabs.

Broadly speaking, two sorts of argument have been put forward in support of measures designed to address poverty abroad. The first is that it is ‘in our interest' to do so: these policies help make the world a safer place and thus safer for our citizens. Economic development also provides greater commercial opportunities for our companies. The second is that this is ‘the right thing to do’. On this view, morality requires us to assist those living in absolute poverty and ensure that all human beings have the basic necessities of life. A key question is whether, and if so, to what extent, international development should be viewed through the prism of its impact on British people. There is consensus, among people working in this field, that aid must also be evaluated in terms of its impact upon the lives of people toward whom it is directed.

In order to tackle global poverty successfully, we must work out what is needed in order for people living in poverty to lead decent lives, establish how these needs can be met (both by their own governments and using outside assistance), and decide what a fair contribution to this effort by the British government would look like. Recent research suggests that additional funds will be needed if the international community is to meet the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the field of health, education and security (Greenhill et al., 2015). In order to meet these targets, the UK may need to raise its contribution well beyond the 0.7 per cent target that OECD countries have already committed to. In addition to financial support, the British government must also seek to mobilize other donors, promote reform of the trade regime, provide access to new technologies, and tackle vested interests in the financial sector that have led to a lax regulatory regime (something that enables illicit financial flows out of developing countries). Taken together, there is widespread recognition that development policy should address poverty in a sustainable way and help people secure their human rights.

In their manifestos, all the political parties recognize the need for the British government to support activities that help people living in extreme poverty overseas. However, their views on international development diverge widely.

At one end of the spectrum is UKIP who endorse a minimalist conception of international development, sticking to the mantra that ‘charity begins at home’. They would close the Department for International Development (DfID), cut the existing development budget significantly from 0.7% of GNI to 0.2%, and spend money only on ‘clean water and sanitation, vaccinations and disaster relief’. UKIP also promises to give the world’s poorest people ‘free access to the British market’. Unfortunately, their agricultural policy takes no account of Britain opening up its agriculture to imports from developing countries.

At the other end of the spectrum is the Green party who proposes a very ambitious set of policies. They propose to raise Britain’s global contribution to 1% of GNI, to focus on the link between human rights and development, to tackle inequality and to promote greater inclusion (both at home and abroad). With regard to climate change the Greens want to go beyond the 2008 Climate Change Act and create ‘a fair global deal that secures humanity’s shared future’. Their position is well researched, builds upon existing evidence, and includes a full budget. Yet questions remain about whether the party’s relatively negative view of the private sector would undermine its revenue forecasts.

Between these two poles lie the Conservative Party, Labour Party, and Liberal Democrats. Each party has relatively progressive proposals when compared to other EU countries, but they focus on extreme poverty reduction, and on UK security and prosperity, as the main goals of international development. Each party agrees that the aid budget should remain at 0.7% of GNI, that the new international Sustainable Development Goals should guide policy, that climate change must be restricted to a maximum rise of two degrees, and that low-skill immigration should be discouraged.

Nonetheless, there are some clear differences. Whereas both Labour and the Liberal Democrats identify human rights as guiding principles, and focus on the whole of government in support of these aims, this is not the case for the Conservatives. Beyond this, the Conservative Party makes no mention of reducing international inequality. Rather, they see aid as a way of promoting British interests, by liberalizing trade rules and opening foreign markets, and of promoting values such as democracy, free media, property rights, open institutions, family planning and gender equality overseas.

There are also differences between Labour and the Liberal Democrats. Labour gives special attention to social inclusion, proposing to establish an International LGBT Rights Envoy and a Centre for Universal Health Coverage, although these points are only flagged briefly. In contrast, the Liberal Democrats and Green manifestos are more sensitive to the problem of paternalism, placing a strong emphasis on empowering people in developing countries and allowing them to decide how they want to pursue these important aims.

Overall, the Green Party manifesto is the most forward-thinking, as it sets aside more resources for international development, proposes more ambitious plans for de-carbonization, and presents a joined-up approach to strategy. They see aid as an expression of solidarity toward justice and greater global equality. In contrast to this, UKIP’s ferocious cutback in funding would, in all likelihood, be very damaging for the world’s poorest people – particularly given that the trade reform they mention is not properly spelled out. The Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrats all defend similar policies. Taken together, they may fail to fully meet the important goals for combatting poverty.

*No UK scoring for the 2 international chapters